A wedding gift for King Louis XIII

Portolan by Joan Oliva. 1615

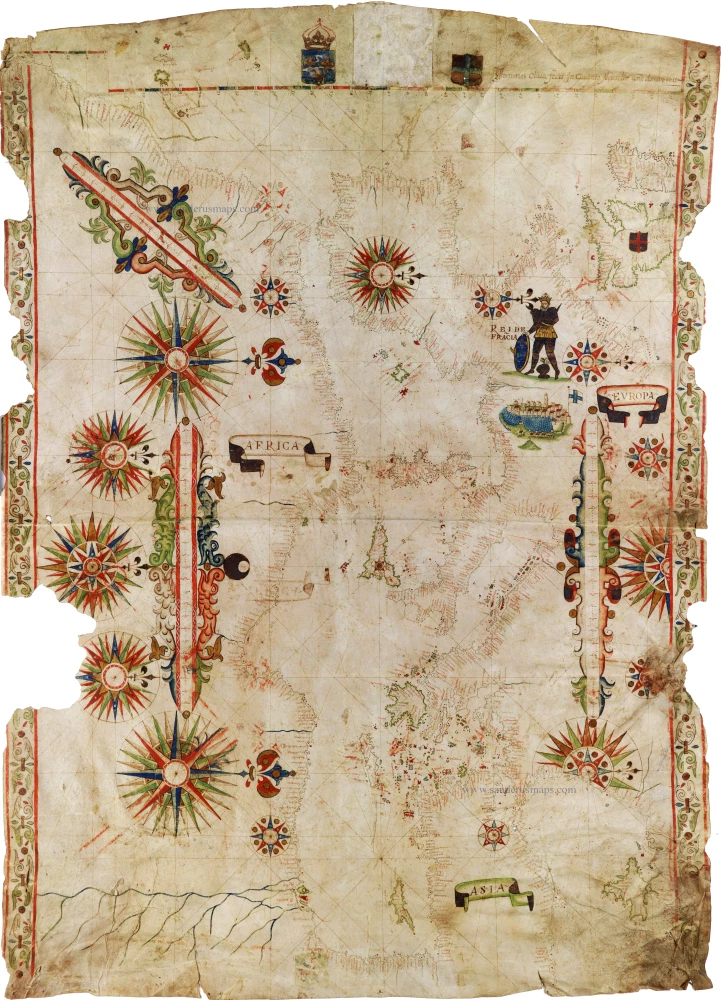

This highly detailed chart encompasses the entire Mediterranean region, with Sicily oriented at center and a big part of Western Europe with the British Isles, coasts of Portugal, Spain, France, the Low Countries and a part of the German sea coast, Including the city of Hamburg ('homborch").

Inscription in upper left-hand corner:

“Joannes Oliva fecit in Civitate Marsilier ano domini 1615”

One of only four extant works from his short chart making period in Marseille, and the only one from this period still in private hands.

Possibly commissioned as a wedding gift for the young French King, Louis XIII. Within the broader tradition of portolan-making, this rare chart of the Mediterranean stands out. It was produced by Joan Oliva, one of the most renowned portolan-makers, at the height of his career.

Key features:

* The chart has been inscribed with the maker’s name and the date of its production, allowing us to identify its origin firmly. According to the annotation, the map was produced by Joan Oliva in 1615. Joan Oliva is perhaps the most prolific, skilled, and renowned member of the famous mapmaking Oliva family (see bio at the bottom). During his illustrious career, Joan Oliva traveled around the Mediterranean, working in Sicily, Mallorca, Livorno, Peloponnesus, and France.

* There was a general progression in the appearance and use of portolan charts during the 16th and 17th centuries. The overall trend was a slow replacement of the portolan tradition by printed maps using new projection models. As a result, there was a shift in the visual qualities of portolan charts, essentially moving them from functional objects to display objects. Joan Oliva's active years fit snugly within this transition, and the progression of his work mirrors this general paradigm shift in portolan cartography.

* Joan Oliva spent at least two critical periods of his career in France. During the first three year stay from ca. 1611-14, Oliva produced a portolan atlas of the highest standard, which included the New World. In early 1615, Oliva returned to France, staying only ten months. During this period, the current portolan was produced, and we propose that the most likely explanation for this was that he returned to France and compiled this map on a direct invitation/commission.

* The portolan stands out from Joan Oliva’s general oeuvre in that it includes some unusual features and omits some otherwise standard features. Among the most important in this regard is the omission of the Oliva family logo, consisting of a Calvary scene on the portolan neck. This chart seemingly does not include such a scene but instead features a heraldic shield with three fleur-de-lis topped by a crown, a straightforward reference to the French King

* The presence of a prominent human figure in the heart of France further underscores the significance of this feature. The central character is armed, in full body armor, and labelled Rei da Franca (King of France). While figurative representations of this kind are not unusual on 17th-century portolan charts, they usually represent geo-political power, not celebrations of a particular ruler, as seems to be the case here. This representation of a single and specific European monarch was uncommon.

* Another standard pictorial inclusion on Joan Oliva’s charts was the depiction of important cities and harbours. These would often include details specific to the harbour they represented, not generic symbols. Such depictions could be used to highlight particular places over others, but the general idea of depicting large port cities would either be applied or not. In this chart, only a single city - Marseille - has been represented. This, however, is shown in impeccable detail, including key features such as its harbour.

* We thus have three salient features that stand out on this chart and which are related directly to the kingship of France: The royal heraldry on the neck, the depiction of the French King as a warrior, and the inclusion of France’s main Mediterranean port as the only depicted city on the map.

Several other features do not relate directly to our interpretation of this chart but are worth highlighting nonetheless:

- While the existence of this portolan is noted in the authoritative MEDEA database (ID no. 2567), there are no images or specifics (dimensions, content, coverage, etc.). This is, in other words, an unstudied chart of considerable historical significance. As such, its reappearance marks an exciting opportunity for new cartographic scholarship.

- The map includes an unusual depiction of the Nile River being fed by tributaries from Egypt’s Eastern Desert.

- The relative positioning of Cyprus and Crete seems to have been resolved. This was an issue of contention at the time, which Oliva had worked on directly. The confusion was related to an emerging understanding of magnetic declination.

- The islands of Rhodes and Chios are still marked with the colours of the Knight Hospitaller/ Malta and Genoa, respectively. This attribution is clearly retrospective, as Rhodes fell to the Ottomans in 1522, and Chios followed in 1566.

- Certain areas on the map have been outlined in a greenish colour, highlighting these from the remaining Mediterranean basin. These include the Mallorca, Sicily, Cyprus, and England islands, as well as the peninsulas of Peloponnese and Crimea.

- The map is decorated with 16 large, elaborate wind roses and three large-scale bars. Compass roses and scale bars are standard decorative elements of a portolan at this stage, but these are of a high aesthetic quality. The same can be said for the ornamental border adorning the top and bottom of the map. The high standard of these decorative elements is indicative that the portolan was explicitly designed for display and that the patron or recipient of this chart would have been among Europe’s absolute elite.

We have noted how Joan Oliva lived and worked in multiple places around the Mediterranean, often staying for years in a given place while he worked on his maps. We know of at least two such working periods in France. During the first stint of three years, Oliva produced one of his finest atlases, which included maps of the New World. This work would have resounded widely around the Mediterranean, especially in France, as the country was eager to join the race to explore and colonize the world. We can imagine that when Oliva returned to France a year later, the esteem was still fresh, and it is in this context that this unusual chart was produced. The evidence that this portolan was made on commission from the highest levels of French society is not only found on the map itself. It can indeed be extrapolated from a number of decisive events in French history during the year 1614-1615:

• In October 1614, King Louis XIII was formally declared of age and fit to rule. He had acceded to the throne in 1610 following the assassination of his father, Henry IV. Until then, King Louis’ Italian mother, Marie de Medici, had served as regent. Even after 1614, she exercised significant control, acting as de facto ruler until her son's reign was fully realized. It was during the regency of Marie de Medici that Oliva spent the first three years in France.

• One of Louis XIII’s first royal acts was to convene the Estates-General. This established form of assembly included representatives from the clergy, nobility, and commoners. It lasted until February 1615, roughly when Oliva arrived in France for the second time. The meeting was called to address financial issues and widespread dissatisfaction among the different social classes. The Estates-General confirmed the authority of Louis XIII as king, but tensions many remained unresolved, highlighting a growing political friction in France. The assembly was largely ineffectual and did not bring about any significant reforms. The fact that it was an unusual thing to do is confirmed by the fact that the Estates-General would not be convened again until 1789, on the eve of the French Revolution.

• Parallel to the Estates-General, there were ongoing marriage negotiations between Louis XIII and Anne of Austria, daughter of King Philip III of Spain. Their marriage in late 1615 was part of a broader diplomatic effort to solidify relations between Europe's two major Catholic powers. Even though both bride and groom were only 14 when they were married, their union had an enormous impact on the political landscape of Europe. Their son, Louis XIV, would become one of France's most famous monarchs.

• Despite the stabilization efforts, young Louis XIII’s authority was not firmly established by his coming of age or by the Estates-General, and 1615 saw significant dissatisfaction and unrest among the French nobility. The main issue was the influence exercised by Marie de Medici and her Italian advisors. This caused some French nobles to challenge the centralization of royal power. This fragmentation was seen as an obvious threat to Louis’ reign.

• In light of the above and consideration of Oliva’s short stay in France during this period, it seems likely that Oliva’s map was commissioned by a pro-Louis party as part of a broader strategy of countering the rebellious nobility.

• Louis XIII’s wedding to Anne of Austria was the most important royal wedding in Europe that year and would have repercussions for decades to come. Considering that the wedding took place at the very end of Oliva’s second stay in France and Oliva’s elevated status as the finest portolan maker of his day, it is our contention that this chart was commissioned as a wedding gift for the young king.

Conclusion:

This chart is of extraordinary quality. It was made during a ten-month stay in France by the most famous portolan-maker at the time. Two years before he began producing this map, Joan Oliva had spent three years in France under the regency of Marie de Medici, young Louis XIII’s mother. During this initial stay, Oliva produced a stunning portolan atlas that included coverage of the New World. The atlas was seen as a seminal achievement, and it is more than likely that Marie de Medici and her Italian advisors would have been privy to it. He returned to France a year later to stay for only ten months, during which he produced the current portolan chart—these ten months coincided with Louis XIII’s official coming of age and his subsequent marriage to Anne of Austria. When this history is juxtaposed with extensive, blatant, and unusual royal symbolism, the best explanation for the origin of this chart was that it was commissioned in late 1614 as a gift for the young king’s upcoming marriage. While we cannot know who commissioned it, the most likely candidates were the king’s supporters, including the Medici Family. Cartographer Bio Joan Oliva came from an extended family of mapmakers that, for multiple generations, dominated the portolan market during the 16th and 17th centuries. The family was originally from Spain and probably arrived in Italy with the Charles V fleet in 1527. At some point, a branch of the family settled in Sicily, where they established their name as leading cartographers in the Messina school. Known charts from the Oliva family span from 1538 to 1673, some of them bearing the signatures of no less than sixteen family members on a single chart. Joan Oliva worked from multiple locations during his lifetime, starting in Messina and probably ending his career in Marseilles. However, the greater Oliva family members have been registered as working in diverse places such as Naples, Livorno, Florence, Venice, Palermo, Messina, Mallorca, and Malta. The extent of the clan and the exact nature of their genealogy remains obscure, but Joan Oliva figures prominently as the family's most prolific and highly regarded mapmaker. Over the 16th and early 17th centuries, he produced some of the most exquisite and rare portolan charts and atlases known to man. We do not know precisely when or where Joan Oliva died, but his output decreased significantly during the 1620s. We know of two charts from 1627 in a private Portuguese collection and a 1629 chart of Sardinia that was compiled by Joan Oliva himself while living in Livorno (Astenga 2007: 180). Joan Oliva may nevertheless have been active well into the 1630s since a chart attributed to him and dated 1634 used to be held in the Biblioteca Trivulziana in Milan. Sadly, this was destroyed, along with most of the extensive map collection, when the library was bombed during World War II. It is, of course, possible that the 1634 and 1636 charts were compiled long after Joan Oliva’s death, but using his notes and drafts.

Some scattered losses, closed tears, and wear along edges; loss in left and right edges affecting compasses and foliate border; residue in top centre edge from sometime removed paper; bottom right edge worn and browned; old central horizontal crease; scattered soiling and surface wear; scattered fading to ink; some faint offsetting from when folded.

Astengo, The Renaissance Chart Tradition in the Mediterranean, p. 233 (this chart mentioned in note 347); Julio Rey Pastor and Ernesto Garcia Camarero, La Cartografia Mallorquina, Madrid, 1960, pp. 137-144; Marcel Destombes, “Francois Ollive et l'Hydrographie Marseillaise au XVII”

Oliva was the most prolific and highly regarded member of the distinguished Oliva family, a mapmaking dynasty that dominated chart-making production in Europe in the 16th to the mid-17th centuries. The family is said to have emigrated in the early 16th century from Majorca, Spain to Italy, and had upwards of 16 members who created nautical charts between 1538 and 1673. Joan's birth and death dates are uncertain, but he is known to have operated out of numerous locations during his life, starting in Italy, in Messina (1592-99), then Naples (1601-03), and then out of Marseille, France (1612-15), where this chart was created in 1615. In 1616 he emigrated to the Tuscan port town of Livorno, where he established his first cartographic studio. Maps from this location date from about 1618-43. Oliva's frequent movements during this period are suggested by Corradino Astengo to indicate that Oliva was a sailor, and "who for fifteen-odd years only occasionally dedicated himself to cartography. It was only after 1618, when he finally settled in Leghorn, that he took up the profession full time for the remainder of his life…” (p. 228)

Portolan makers were typically drawn to bustling port cities where their charts became invaluable to ships captains. Marseille became an important port during the mid-16th century due to increased trade with the East, attracting cartographers from around the Mediterranean, such as the Oliva, Roussin, and Bremond families, who dominated chart-making there until the end of the 17th century.

Oliva's extant works total about 40 or more charts or atlases. This chart is one of only four known extant works from his time in France. The other 3 extant works from his time in Marseille are two atlases (1613 and 1614) and one nautical chart (1612). These are held at the British Library, the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples, and at the Museo Storico Navale in Venice, respectively.

An intricate network of sepia ink rhumb lines criss-crosses the entire chart, emanating from 16 colourful wind compasses, while three large scale bars with colourful arabesque borders extend along the coasts of North and Northwest Africa and Europe. Hundreds of coastal towns and ports are identified by name, largely in Italian, with larger locales written in red ink, and secondary, or smaller locations written in sepia ink. Large peninsulas such as the Crimea and Peloponnese, as well as islands such as Sicily, Cyprus, England, and Mallorca, are outlined in green ink, with smaller islands painted in alternating green and red inks. Over the islands of Malta, Rhodes, and Chios a cross is shown in red. Major rivers feeding into the Mediterranean are shown in blue ink, such as the Nile, which extends to the map's lower right edge. Pictorial elements adorn the map, such as the Royal arms of France at the top edge, a shield with the arms of Marseille to the left of Oliva's inscription, and a shield with the arms of St. George over England's landmass. At the centre of France's landmass can be seen a view of Marseille, under an armoured figure with shield and sword (of a French sovereign, likely King Louis XIII ) with “Reide Fracia” (King of France) in manuscript.

Special thanks to Michael Jennings from Neatline maps for his research and the description of this Portolan.

Provenance:

Sotheby's auction, New York, Fine Books and Manuscripts, May 22, 1985, Sale 5330, Lot 122.

Private collection in the USA, 1985 - 2024.

Freeman's & Hindman auction, Philadelphia, Books and Manuscripts, June 25, 2024, Lot 82.

back

Marseille, 1615.

€185000

($214600 / £160950)

add to cart

Buy now

questions?

PRINT

Item Number: 31021 Authenticity Guarantee

Category: Antique maps > Europe > Europe Continent

Joan Oliva, Portolan Chart of Europe

Marseille, 1615.

Illuminated manuscript portolan chart on vellum, in red, blue, green, and sepia inks, heightened in gold; 16 wind compasses; three large scale bars; within foliate border at top and bottom edge; place names executed in a small neat hand in red and sepia inks; shield with royal arms of France at left, shield with arms of Marseille at same; shield with Cross of St. George at left; verso blank; 781 x 559 mm (30 3/4 x 22 in).

This highly detailed chart encompasses the entire Mediterranean region, with Sicily oriented at center and a big part of Western Europe with the British Isles, coasts of Portugal, Spain, France, the Low Countries and a part of the German sea coast, Including the city of Hamburg ('homborch").

Inscription in upper left-hand corner:

“Joannes Oliva fecit in Civitate Marsilier ano domini 1615”

One of only four extant works from his short chart making period in Marseille, and the only one from this period still in private hands.

Possibly commissioned as a wedding gift for the young French King, Louis XIII. Within the broader tradition of portolan-making, this rare chart of the Mediterranean stands out. It was produced by Joan Oliva, one of the most renowned portolan-makers, at the height of his career.

Key features:

* The chart has been inscribed with the maker’s name and the date of its production, allowing us to identify its origin firmly. According to the annotation, the map was produced by Joan Oliva in 1615. Joan Oliva is perhaps the most prolific, skilled, and renowned member of the famous mapmaking Oliva family (see bio at the bottom). During his illustrious career, Joan Oliva traveled around the Mediterranean, working in Sicily, Mallorca, Livorno, Peloponnesus, and France.

* There was a general progression in the appearance and use of portolan charts during the 16th and 17th centuries. The overall trend was a slow replacement of the portolan tradition by printed maps using new projection models. As a result, there was a shift in the visual qualities of portolan charts, essentially moving them from functional objects to display objects. Joan Oliva's active years fit snugly within this transition, and the progression of his work mirrors this general paradigm shift in portolan cartography.

* Joan Oliva spent at least two critical periods of his career in France. During the first three year stay from ca. 1611-14, Oliva produced a portolan atlas of the highest standard, which included the New World. In early 1615, Oliva returned to France, staying only ten months. During this period, the current portolan was produced, and we propose that the most likely explanation for this was that he returned to France and compiled this map on a direct invitation/commission.

* The portolan stands out from Joan Oliva’s general oeuvre in that it includes some unusual features and omits some otherwise standard features. Among the most important in this regard is the omission of the Oliva family logo, consisting of a Calvary scene on the portolan neck. This chart seemingly does not include such a scene but instead features a heraldic shield with three fleur-de-lis topped by a crown, a straightforward reference to the French King

* The presence of a prominent human figure in the heart of France further underscores the significance of this feature. The central character is armed, in full body armor, and labelled Rei da Franca (King of France). While figurative representations of this kind are not unusual on 17th-century portolan charts, they usually represent geo-political power, not celebrations of a particular ruler, as seems to be the case here. This representation of a single and specific European monarch was uncommon.

* Another standard pictorial inclusion on Joan Oliva’s charts was the depiction of important cities and harbours. These would often include details specific to the harbour they represented, not generic symbols. Such depictions could be used to highlight particular places over others, but the general idea of depicting large port cities would either be applied or not. In this chart, only a single city - Marseille - has been represented. This, however, is shown in impeccable detail, including key features such as its harbour.

* We thus have three salient features that stand out on this chart and which are related directly to the kingship of France: The royal heraldry on the neck, the depiction of the French King as a warrior, and the inclusion of France’s main Mediterranean port as the only depicted city on the map.

Several other features do not relate directly to our interpretation of this chart but are worth highlighting nonetheless:

- While the existence of this portolan is noted in the authoritative MEDEA database (ID no. 2567), there are no images or specifics (dimensions, content, coverage, etc.). This is, in other words, an unstudied chart of considerable historical significance. As such, its reappearance marks an exciting opportunity for new cartographic scholarship.

- The map includes an unusual depiction of the Nile River being fed by tributaries from Egypt’s Eastern Desert.

- The relative positioning of Cyprus and Crete seems to have been resolved. This was an issue of contention at the time, which Oliva had worked on directly. The confusion was related to an emerging understanding of magnetic declination.

- The islands of Rhodes and Chios are still marked with the colours of the Knight Hospitaller/ Malta and Genoa, respectively. This attribution is clearly retrospective, as Rhodes fell to the Ottomans in 1522, and Chios followed in 1566.

- Certain areas on the map have been outlined in a greenish colour, highlighting these from the remaining Mediterranean basin. These include the Mallorca, Sicily, Cyprus, and England islands, as well as the peninsulas of Peloponnese and Crimea.

- The map is decorated with 16 large, elaborate wind roses and three large-scale bars. Compass roses and scale bars are standard decorative elements of a portolan at this stage, but these are of a high aesthetic quality. The same can be said for the ornamental border adorning the top and bottom of the map. The high standard of these decorative elements is indicative that the portolan was explicitly designed for display and that the patron or recipient of this chart would have been among Europe’s absolute elite.

We have noted how Joan Oliva lived and worked in multiple places around the Mediterranean, often staying for years in a given place while he worked on his maps. We know of at least two such working periods in France. During the first stint of three years, Oliva produced one of his finest atlases, which included maps of the New World. This work would have resounded widely around the Mediterranean, especially in France, as the country was eager to join the race to explore and colonize the world. We can imagine that when Oliva returned to France a year later, the esteem was still fresh, and it is in this context that this unusual chart was produced. The evidence that this portolan was made on commission from the highest levels of French society is not only found on the map itself. It can indeed be extrapolated from a number of decisive events in French history during the year 1614-1615:

• In October 1614, King Louis XIII was formally declared of age and fit to rule. He had acceded to the throne in 1610 following the assassination of his father, Henry IV. Until then, King Louis’ Italian mother, Marie de Medici, had served as regent. Even after 1614, she exercised significant control, acting as de facto ruler until her son's reign was fully realized. It was during the regency of Marie de Medici that Oliva spent the first three years in France.

• One of Louis XIII’s first royal acts was to convene the Estates-General. This established form of assembly included representatives from the clergy, nobility, and commoners. It lasted until February 1615, roughly when Oliva arrived in France for the second time. The meeting was called to address financial issues and widespread dissatisfaction among the different social classes. The Estates-General confirmed the authority of Louis XIII as king, but tensions many remained unresolved, highlighting a growing political friction in France. The assembly was largely ineffectual and did not bring about any significant reforms. The fact that it was an unusual thing to do is confirmed by the fact that the Estates-General would not be convened again until 1789, on the eve of the French Revolution.

• Parallel to the Estates-General, there were ongoing marriage negotiations between Louis XIII and Anne of Austria, daughter of King Philip III of Spain. Their marriage in late 1615 was part of a broader diplomatic effort to solidify relations between Europe's two major Catholic powers. Even though both bride and groom were only 14 when they were married, their union had an enormous impact on the political landscape of Europe. Their son, Louis XIV, would become one of France's most famous monarchs.

• Despite the stabilization efforts, young Louis XIII’s authority was not firmly established by his coming of age or by the Estates-General, and 1615 saw significant dissatisfaction and unrest among the French nobility. The main issue was the influence exercised by Marie de Medici and her Italian advisors. This caused some French nobles to challenge the centralization of royal power. This fragmentation was seen as an obvious threat to Louis’ reign.

• In light of the above and consideration of Oliva’s short stay in France during this period, it seems likely that Oliva’s map was commissioned by a pro-Louis party as part of a broader strategy of countering the rebellious nobility.

• Louis XIII’s wedding to Anne of Austria was the most important royal wedding in Europe that year and would have repercussions for decades to come. Considering that the wedding took place at the very end of Oliva’s second stay in France and Oliva’s elevated status as the finest portolan maker of his day, it is our contention that this chart was commissioned as a wedding gift for the young king.

Conclusion:

This chart is of extraordinary quality. It was made during a ten-month stay in France by the most famous portolan-maker at the time. Two years before he began producing this map, Joan Oliva had spent three years in France under the regency of Marie de Medici, young Louis XIII’s mother. During this initial stay, Oliva produced a stunning portolan atlas that included coverage of the New World. The atlas was seen as a seminal achievement, and it is more than likely that Marie de Medici and her Italian advisors would have been privy to it. He returned to France a year later to stay for only ten months, during which he produced the current portolan chart—these ten months coincided with Louis XIII’s official coming of age and his subsequent marriage to Anne of Austria. When this history is juxtaposed with extensive, blatant, and unusual royal symbolism, the best explanation for the origin of this chart was that it was commissioned in late 1614 as a gift for the young king’s upcoming marriage. While we cannot know who commissioned it, the most likely candidates were the king’s supporters, including the Medici Family. Cartographer Bio Joan Oliva came from an extended family of mapmakers that, for multiple generations, dominated the portolan market during the 16th and 17th centuries. The family was originally from Spain and probably arrived in Italy with the Charles V fleet in 1527. At some point, a branch of the family settled in Sicily, where they established their name as leading cartographers in the Messina school. Known charts from the Oliva family span from 1538 to 1673, some of them bearing the signatures of no less than sixteen family members on a single chart. Joan Oliva worked from multiple locations during his lifetime, starting in Messina and probably ending his career in Marseilles. However, the greater Oliva family members have been registered as working in diverse places such as Naples, Livorno, Florence, Venice, Palermo, Messina, Mallorca, and Malta. The extent of the clan and the exact nature of their genealogy remains obscure, but Joan Oliva figures prominently as the family's most prolific and highly regarded mapmaker. Over the 16th and early 17th centuries, he produced some of the most exquisite and rare portolan charts and atlases known to man. We do not know precisely when or where Joan Oliva died, but his output decreased significantly during the 1620s. We know of two charts from 1627 in a private Portuguese collection and a 1629 chart of Sardinia that was compiled by Joan Oliva himself while living in Livorno (Astenga 2007: 180). Joan Oliva may nevertheless have been active well into the 1630s since a chart attributed to him and dated 1634 used to be held in the Biblioteca Trivulziana in Milan. Sadly, this was destroyed, along with most of the extensive map collection, when the library was bombed during World War II. It is, of course, possible that the 1634 and 1636 charts were compiled long after Joan Oliva’s death, but using his notes and drafts.

Some scattered losses, closed tears, and wear along edges; loss in left and right edges affecting compasses and foliate border; residue in top centre edge from sometime removed paper; bottom right edge worn and browned; old central horizontal crease; scattered soiling and surface wear; scattered fading to ink; some faint offsetting from when folded.

Astengo, The Renaissance Chart Tradition in the Mediterranean, p. 233 (this chart mentioned in note 347); Julio Rey Pastor and Ernesto Garcia Camarero, La Cartografia Mallorquina, Madrid, 1960, pp. 137-144; Marcel Destombes, “Francois Ollive et l'Hydrographie Marseillaise au XVII”

Oliva was the most prolific and highly regarded member of the distinguished Oliva family, a mapmaking dynasty that dominated chart-making production in Europe in the 16th to the mid-17th centuries. The family is said to have emigrated in the early 16th century from Majorca, Spain to Italy, and had upwards of 16 members who created nautical charts between 1538 and 1673. Joan's birth and death dates are uncertain, but he is known to have operated out of numerous locations during his life, starting in Italy, in Messina (1592-99), then Naples (1601-03), and then out of Marseille, France (1612-15), where this chart was created in 1615. In 1616 he emigrated to the Tuscan port town of Livorno, where he established his first cartographic studio. Maps from this location date from about 1618-43. Oliva's frequent movements during this period are suggested by Corradino Astengo to indicate that Oliva was a sailor, and "who for fifteen-odd years only occasionally dedicated himself to cartography. It was only after 1618, when he finally settled in Leghorn, that he took up the profession full time for the remainder of his life…” (p. 228)

Portolan makers were typically drawn to bustling port cities where their charts became invaluable to ships captains. Marseille became an important port during the mid-16th century due to increased trade with the East, attracting cartographers from around the Mediterranean, such as the Oliva, Roussin, and Bremond families, who dominated chart-making there until the end of the 17th century.

Oliva's extant works total about 40 or more charts or atlases. This chart is one of only four known extant works from his time in France. The other 3 extant works from his time in Marseille are two atlases (1613 and 1614) and one nautical chart (1612). These are held at the British Library, the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples, and at the Museo Storico Navale in Venice, respectively.

An intricate network of sepia ink rhumb lines criss-crosses the entire chart, emanating from 16 colourful wind compasses, while three large scale bars with colourful arabesque borders extend along the coasts of North and Northwest Africa and Europe. Hundreds of coastal towns and ports are identified by name, largely in Italian, with larger locales written in red ink, and secondary, or smaller locations written in sepia ink. Large peninsulas such as the Crimea and Peloponnese, as well as islands such as Sicily, Cyprus, England, and Mallorca, are outlined in green ink, with smaller islands painted in alternating green and red inks. Over the islands of Malta, Rhodes, and Chios a cross is shown in red. Major rivers feeding into the Mediterranean are shown in blue ink, such as the Nile, which extends to the map's lower right edge. Pictorial elements adorn the map, such as the Royal arms of France at the top edge, a shield with the arms of Marseille to the left of Oliva's inscription, and a shield with the arms of St. George over England's landmass. At the centre of France's landmass can be seen a view of Marseille, under an armoured figure with shield and sword (of a French sovereign, likely King Louis XIII ) with “Reide Fracia” (King of France) in manuscript.

Special thanks to Michael Jennings from Neatline maps for his research and the description of this Portolan.

Provenance:

Sotheby's auction, New York, Fine Books and Manuscripts, May 22, 1985, Sale 5330, Lot 122.

Private collection in the USA, 1985 - 2024.

Freeman's & Hindman auction, Philadelphia, Books and Manuscripts, June 25, 2024, Lot 82.