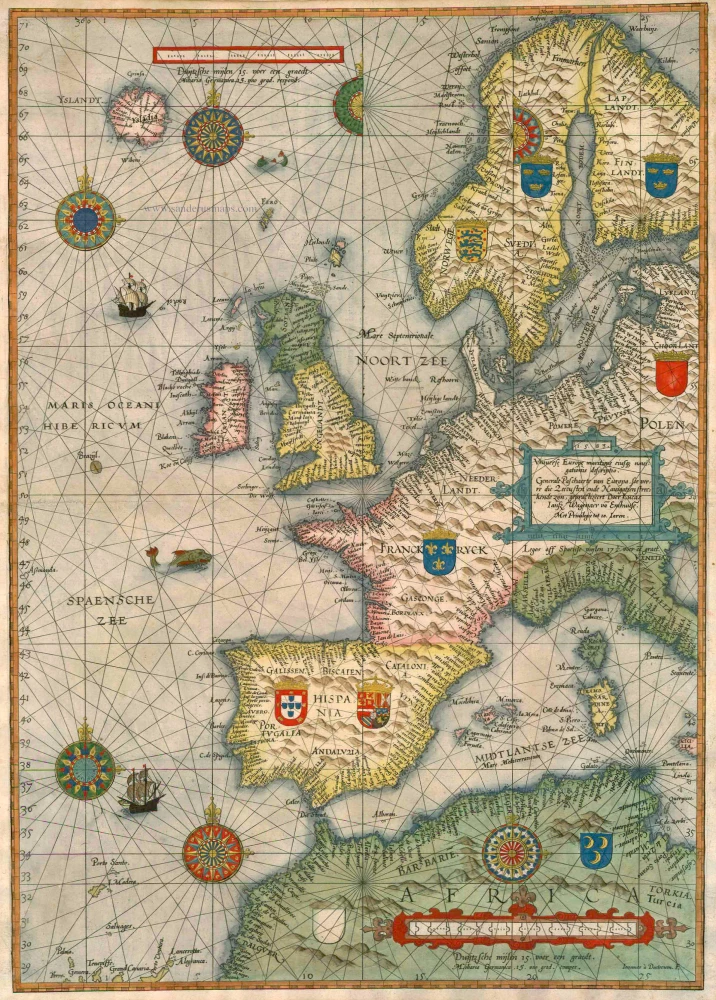

Antique map of Europe by Waghenaer L.J. 1586

Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer (c. 1533 – 1606)

Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer grew up in Enkhuizen, a fishing port in the Netherlands on the Zuiderzee. It is known that around 1570, Waghenaer was already involved in drawing sea charts. The first indication of his cartographic activity was the plan of the town, engraved by Harmen Hansz. Muller of Amsterdam and dated 2 February. 1577.

In 1579, he gave up his career as a maritime pilot and obtained a post in the town. At the same time, he prepared his chartbook. Cutting the plates cost Waghenaer a large sum. He constantly sought loans and had to accept small jobs to help him earn a living. In the wealthy town of Enkhuizen, he was a poor man, seeking support in every direction and trusting in the success of his significant undertaking: the edition of the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt.

In 1583, the first part of the 'Spieghel' went to press in Plantijn's then-recently established printing house in Leiden. He dedicated the work to Prince William of Orange.

On 25 January 1584, he had a formal certificate drawn up before a notary: they attested the charts' reliability and originality in the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt.

Waghenaer continued to work on completing the second volume of the Spieghel. In the meantime, the first volume met with considerable success and was reprinted several times during the first two years. The work was reprinted regularly and was also very popular in England. Waghenaer had already become a famous man.

Soon after his Spieghel appeared, he formulated a plan to publish an improved "rutter of the sea'. This was to become the Thresoor der Zeevaerdt of 1592.

In addition to the revenue from his books, he received additional income from the sale of loose portolan charts. In 1580, he was granted a patent for two large charts of the coasts of Europe. One of these portolan charts is the general map from the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt of 1584 and later editions.

In 1592, Jan Huygen van Linschoten settled in the town and wrote the journal of his voyages in Asia, which he published in 1596. In addition, Van Linschoten helped Waghenaer compile another new seaman's guide: the Enchuyser Zeecaertboeck, which had important information about Northern Europe's coasts.

In 1598, Waghenaer was appointed as a commission member to find a method of determining longitude at sea. Unfortunately, he must have been in financial difficulties for the last years of his life. He died in 1606, leaving his widow in dire circumstances.

............................................................................................ The Spieghel der Zeevaerdt or Speculum nauticum super navigatione holds a unique place among the printed rutters of the sea in the 16th century because it is the first printed rutter with charts. Further, it outranks any other rutter of its period with its splendid presentation of charts and text; as such, it stood as a model for the folio-size pilot guides with charts in the 17th century.

However, format and typography needed to be more balanced according to the taste of the practical navigators of that time and Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer returned to the traditional, more modest rutter in the oblong format, The Thresoor der Zeevaert, in 1592.

Thanks to the unparalleled skill of the engravers, Baptist and Johannes van Deutecom, the original ms. charts by Waghenaer were transformed into the most beautiful maps of the period.

The composition and the adornment have contributed significantly to the splendour of what initially were simple sketch charts; the typography of the Plantijn printing house at Leiden further added to the book's quality. In its concept, the text follows the traditional composition of the 16th-century pilot guides, but the charts form a new element. One remarkable feature is the coastal profiles projected onto the land along the coasts, further elucidated by profiles drawn in the charts' open areas. There is no evidence that Waghenaer copied his charts from existing sources. Some of them must have been based on his observations, and for the whole work, he must have relied on his rich experience in practical navigation.

Universe Europae Maritime eiusque Navigationis Descriptio

Item Number: 5424 Authenticity Guarantee

Category: Antique maps > Oceans

First state of one of the most beautiful portolan charts of Europe.

Copper engraving

Size: 56 x 39.5cm (21.8 x 15.4 inches)

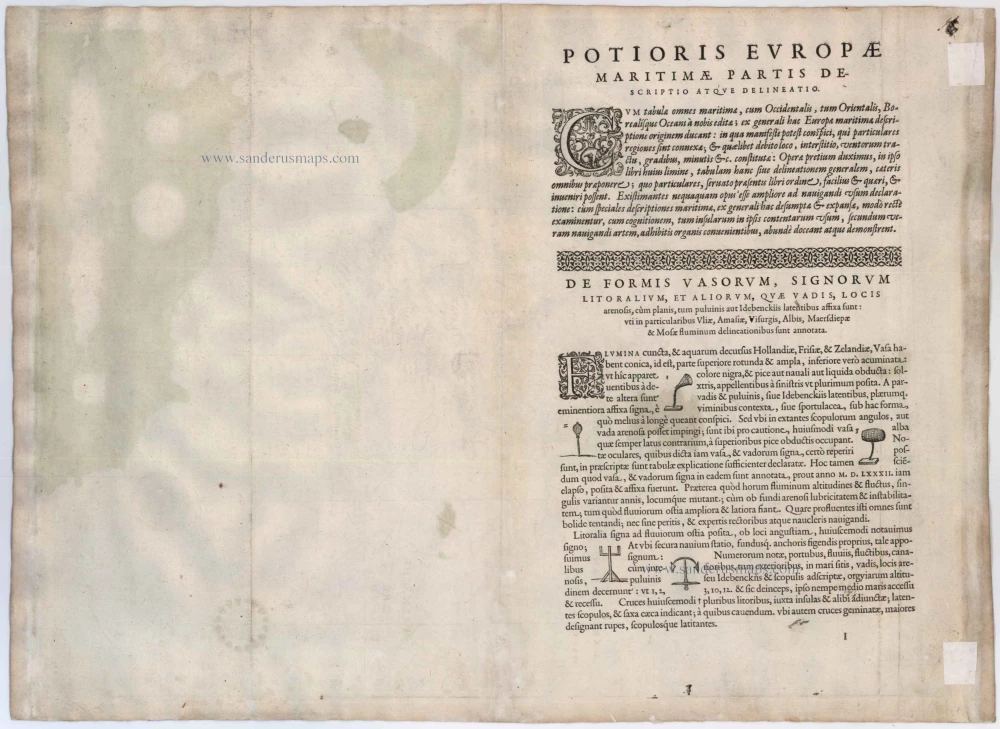

Verso text: Latin

Condition: Old coloured, new upper and lower margins with reinstatement of parts of the grade scale.

Condition Rating: B

References: Koeman, Wag 1A; Campbell, Early Maps, p.86, pl.39; Baynton-Williams New Worlds, p.40; Bifolco, Mare Nostrum, Tav. 16.

From: Speculum nauticum super navigatione maris Occidentalis confectum, continens omnes oras maritimas Galliae, Hispaniae et praecipuarum partiu Angliae, ... - Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, vande navigatie der Westersche zee Innehoudende alle de Custen van Franckrijck, Spaignen, en t' principaelste deel van Engelandt, ... Lugduni Batavorum (Leiden), Excudebat typis Plantiniannis Franciscus Raphelengius, pro Luca Ioannis Aurigario. MDLXXXVI (1586). (Koeman IV, Wag5A)

This work holds a unique place among the printed rutters of the sea in the 16th century because it is the first printed rutter with charts. Further, it outranks any other rutter of its period, with its splendid presentation of charts and text; as such it stood as a model for the folio-size pilot-guides with charts in the 17th century.

Thanks to the unparalleled skill of the engravers, Baptist and Johannes van Deutecom, the original ms. charts by Waghenaer were transformed into the most beautiful maps of the period. The composition and the adornment have greatly contributed to the splendour of what originally were simple sketch-charts; the typography of the Plantijn printing house at Leiden further added to the quality of the book.

In its concept, the text follows the traditional composition of the 16th century pilot-guides but the charts form a new element. One remarkable feature is the coastal profiles projected onto the land along the coasts, further elucidated by profiles drawn in the open areas of the charts. There is no evidence that Waghenaer copied his charts from existing sources. Some of them must have been based on his personal observations and for the whole of the work he must have relied on his own rich experience in practical navigation. (Koeman)

Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer (c. 1533 – 1606)

Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer grew up in Enkhuizen, a fishing port in the Netherlands on the Zuiderzee. It is known that around 1570, Waghenaer was already involved in drawing sea charts. The first indication of his cartographic activity was the plan of the town, engraved by Harmen Hansz. Muller of Amsterdam and dated 2 February. 1577.

In 1579, he gave up his career as a maritime pilot and obtained a post in the town. At the same time, he prepared his chartbook. Cutting the plates cost Waghenaer a large sum. He constantly sought loans and had to accept small jobs to help him earn a living. In the wealthy town of Enkhuizen, he was a poor man, seeking support in every direction and trusting in the success of his significant undertaking: the edition of the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt.

In 1583, the first part of the 'Spieghel' went to press in Plantijn's then-recently established printing house in Leiden. He dedicated the work to Prince William of Orange.

On 25 January 1584, he had a formal certificate drawn up before a notary: they attested the charts' reliability and originality in the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt.

Waghenaer continued to work on completing the second volume of the Spieghel. In the meantime, the first volume met with considerable success and was reprinted several times during the first two years. The work was reprinted regularly and was also very popular in England. Waghenaer had already become a famous man.

Soon after his Spieghel appeared, he formulated a plan to publish an improved "rutter of the sea'. This was to become the Thresoor der Zeevaerdt of 1592.

In addition to the revenue from his books, he received additional income from the sale of loose portolan charts. In 1580, he was granted a patent for two large charts of the coasts of Europe. One of these portolan charts is the general map from the Spieghel der Zeevaerdt of 1584 and later editions.

In 1592, Jan Huygen van Linschoten settled in the town and wrote the journal of his voyages in Asia, which he published in 1596. In addition, Van Linschoten helped Waghenaer compile another new seaman's guide: the Enchuyser Zeecaertboeck, which had important information about Northern Europe's coasts.

In 1598, Waghenaer was appointed as a commission member to find a method of determining longitude at sea. Unfortunately, he must have been in financial difficulties for the last years of his life. He died in 1606, leaving his widow in dire circumstances.

............................................................................................ The Spieghel der Zeevaerdt or Speculum nauticum super navigatione holds a unique place among the printed rutters of the sea in the 16th century because it is the first printed rutter with charts. Further, it outranks any other rutter of its period with its splendid presentation of charts and text; as such, it stood as a model for the folio-size pilot guides with charts in the 17th century.

However, format and typography needed to be more balanced according to the taste of the practical navigators of that time and Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer returned to the traditional, more modest rutter in the oblong format, The Thresoor der Zeevaert, in 1592.

Thanks to the unparalleled skill of the engravers, Baptist and Johannes van Deutecom, the original ms. charts by Waghenaer were transformed into the most beautiful maps of the period.

The composition and the adornment have contributed significantly to the splendour of what initially were simple sketch charts; the typography of the Plantijn printing house at Leiden further added to the book's quality. In its concept, the text follows the traditional composition of the 16th-century pilot guides, but the charts form a new element. One remarkable feature is the coastal profiles projected onto the land along the coasts, further elucidated by profiles drawn in the charts' open areas. There is no evidence that Waghenaer copied his charts from existing sources. Some of them must have been based on his observations, and for the whole work, he must have relied on his rich experience in practical navigation.