Luxury colour

Straits of Magellan by Joannes Janssonius. 1653-66

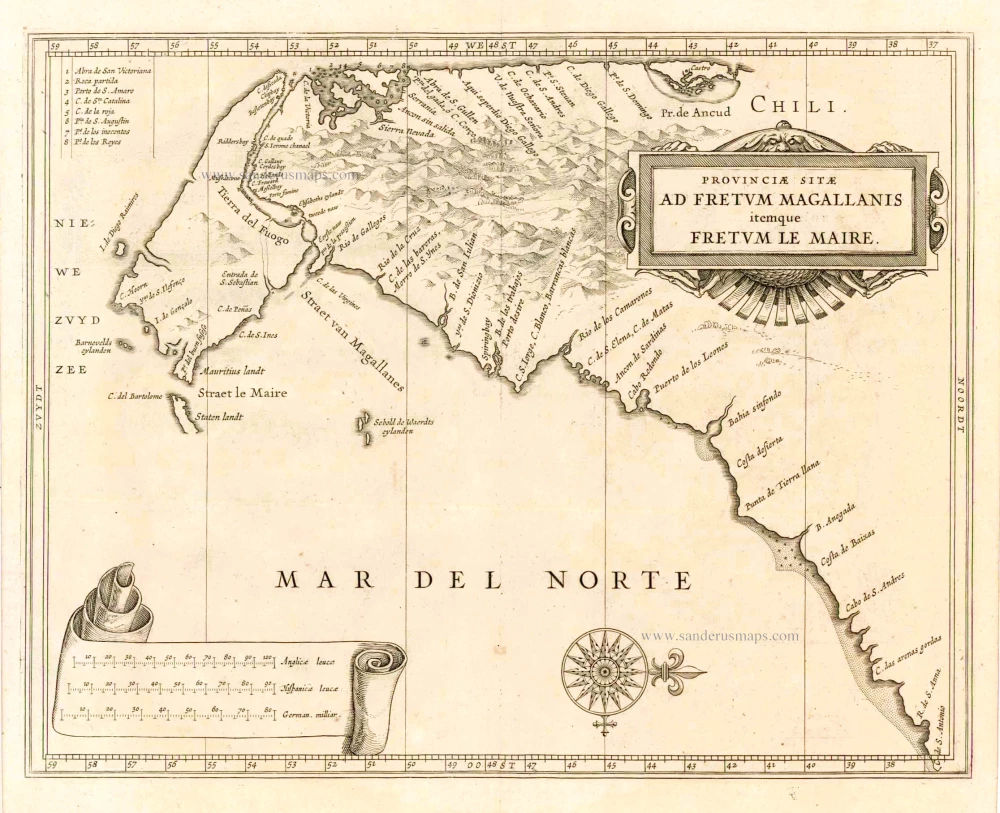

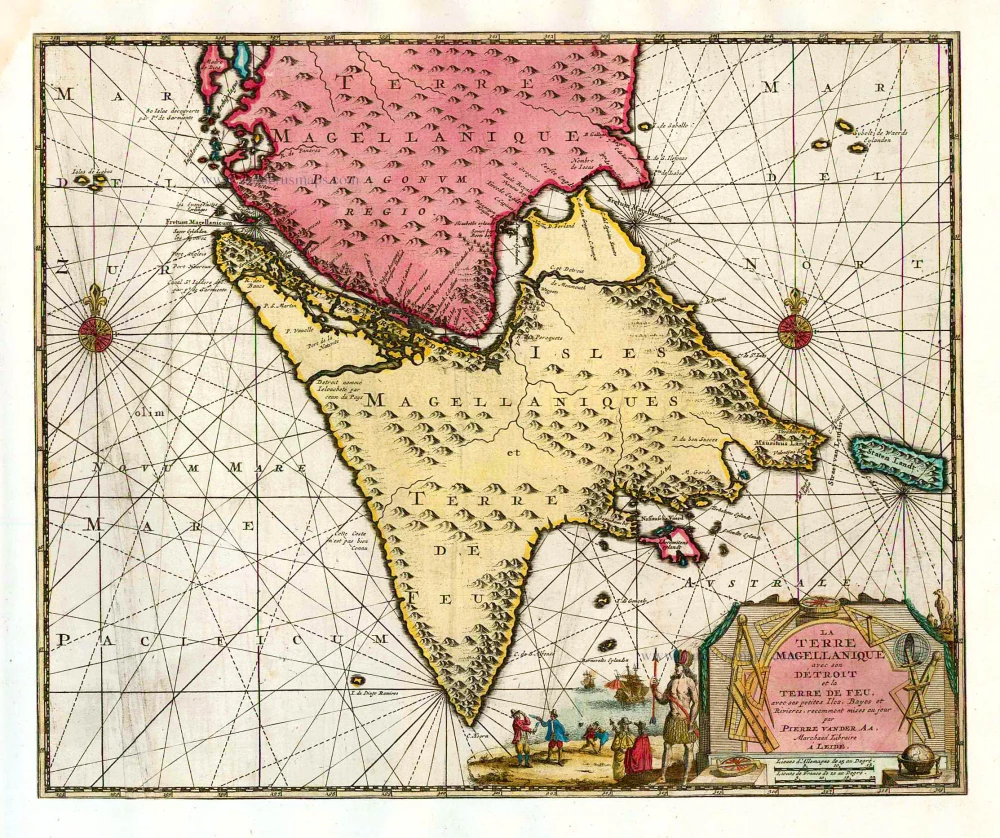

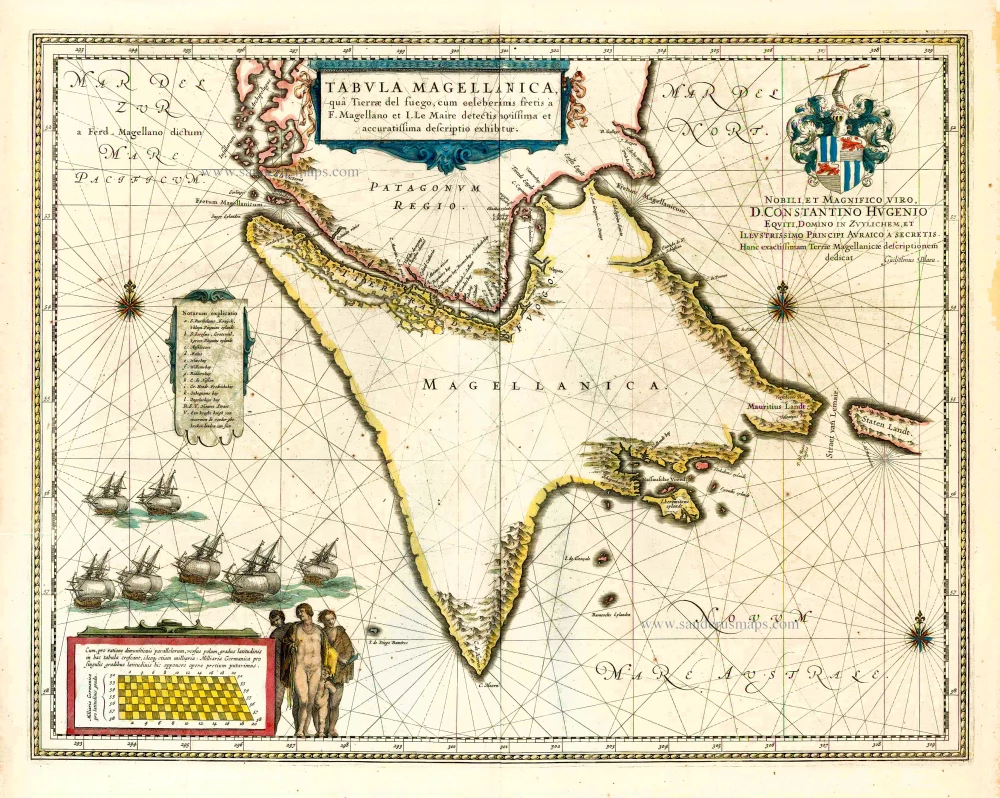

To the men of the 17th century, Tierra del Fuego, the group of islands south of the Straits of Magellan, was one of the most desolate parts of the world. The frequently printed maps of this region - which they called Magellanica - did not reflect an interest in the area for its own sake but rather depicted two of the three westerly passages to the East Indies. The other route, an unhealthy portage across the Isthmus of Panama, was under tight Spanish control.

Seaways to the East are the key to understanding most early explorations. With the passage around the Cape of Good Hoop controlled by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century and by the licensed Dutch, English, and French East India Companies thereafter, there was a strong incentive for would-be competitors to look elsewhere. Janssonius' chart describes both the route Ferdinand Magellan pioneered through his strait in 1520 and the Cape Horn passage that had been successfully navigated by two Dutchmen, Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire, in 1616.

Although Spain laid claim to the Straits of Magellan, in practice, the obstacles of these routes were natural rather than political. The terrors of Cape Horn are legendary, but the Strait was no alternative. Its narrow channels, strong currents, and unpredictable winds tested sailing ships to the limit. In addition, chunks of the glaciers lined the passage might break off at any time and join the icebergs that already littered the channel.

It is not surprising, therefore, that sailors should add imaginary dangers to the real ones, peopling the land to the north of the Straits with giants. Magellan called the natives "Patagoni" (or big feet), and his chronicler Antonio Pigafetta recorded seeing "a naked man of giant stature ... so tall that we reached only to his waist." The Dutch discoverers of Cape Horn a century later gave substance to the legend when they found the bones of a man they believed to have been over 3 m high. Jansson, however, is disappointingly discreet, filling out his chart with plausible-looking natives, rheas (the South American ostrich that they hunted with bows and spears), and penguins.

The checkerboard in the lower left corner is not evidence of local sophistication but rather represents a variable scale. This enabled sailors to counteract the increasingly exaggerated distances caused by high latitudes using Mercator's projection. (Campbell)

The Janssonius Family

Joannes Janssonius (Arnhem, 1588-1664), son of the Arnhem publisher Jan Janssen, married Elisabeth Hondius, daughter of Jodocus Hondius, in Amsterdam in 1612. After his marriage, he settled down in this town as a bookseller and publisher of cartographic material. In 1618, he established himself in Amsterdam next door to Blaeu’s bookshop. He entered into serious competition with Willem Jansz. Blaeu when copying Blaeu’s Licht der Zeevaert after the expiration of the privilege in 1620. His activities concerned the publication of atlases, books, single maps, and an extensive book trade with branches in Frankfurt, Danzig, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Berlin, Koningsbergen, Geneva, and Lyon. In 1631, he began publishing atlases together with Henricus Hondius.

In the early 1640s, Henricus Hondius left the atlas publishing business to Janssonius. Competition with Joan Blaeu, Willem’s son and successor, in atlas production, prompted Janssonius to enlarge his Atlas Novus finally into a work of six volumes, into which a sea atlas and an atlas of the Old World were inserted. Other atlases published by Janssonius are Mercator’s Atlas Minor, Hornius’s historical atlas (1652), the townbooks in eight volumes (1657), Cellarius’s Atlas Coelestis and several sea atlases and pilot guides.

After the death of Joannes Janssonius, the shop and publishing firm were continued by the heirs under the direction of Johannes van Waesbergen (c. 1616-1681), son-in-law of Joannes Janssonius. Van Waesbergen added Janssonius's name to his own.

In 1676, Joannes Janssonius’s heirs sold by auction “all the remaining Atlases in Latin, French, High and Low German, as well as the Stedeboecken in Latin, in 8 volumes, bound and unbound, maps, plates belonging to the Atlas and Stedeboecken.” The copperplates from Janssonius’s atlases were afterwards sold to Schenk and Valck.

Tabula Magellanica qua Tierrae del Fuego.

Item Number: 29805 new Authenticity Guarantee

Category: Antique maps > America > South America

Old, antique map of the Straits of Magellan by Joannes Janssonius.

Title: Tabula Magellanica qua Tierrae del Fuego.

Cum celeberrimus fretis a F. Magellano et I. Le Maire detectis

Novißima et accuratißima descriptio exhibetur.

Amstelodami, Apud Joannem Janßonium.

Dedication to Gualtherus de Raet by Joannes Janssonius.

Date of the first edition: 1645.

Date of this map: 1653-66.

Copper engraving, printed on paper.

Image size: 410 x 530mm (16.14 x 20.87 inches).

Sheet size: 515 x 605mm (20.28 x 23.82 inches).

Verso: Spanish text.

Condition: Original coloured, excellent.

Condition Rating: A+.

From: Nuevo Atlas, o Teatro de Todo el Mundo de Juan Janssoniu en el qual con gran Cuydado Se Prponen los Mapas y Descripciones de Tode el Universo. Amsterdam, J. Janssonius, 1653-66.

To the men of the 17th century, Tierra del Fuego, the group of islands south of the Straits of Magellan, was one of the most desolate parts of the world. The frequently printed maps of this region - which they called Magellanica - did not reflect an interest in the area for its own sake but rather depicted two of the three westerly passages to the East Indies. The other route, an unhealthy portage across the Isthmus of Panama, was under tight Spanish control.

Seaways to the East are the key to understanding most early explorations. With the passage around the Cape of Good Hoop controlled by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century and by the licensed Dutch, English, and French East India Companies thereafter, there was a strong incentive for would-be competitors to look elsewhere. Janssonius' chart describes both the route Ferdinand Magellan pioneered through his strait in 1520 and the Cape Horn passage that had been successfully navigated by two Dutchmen, Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire, in 1616.

Although Spain laid claim to the Straits of Magellan, in practice, the obstacles of these routes were natural rather than political. The terrors of Cape Horn are legendary, but the Strait was no alternative. Its narrow channels, strong currents, and unpredictable winds tested sailing ships to the limit. In addition, chunks of the glaciers lined the passage might break off at any time and join the icebergs that already littered the channel.

It is not surprising, therefore, that sailors should add imaginary dangers to the real ones, peopling the land to the north of the Straits with giants. Magellan called the natives "Patagoni" (or big feet), and his chronicler Antonio Pigafetta recorded seeing "a naked man of giant stature ... so tall that we reached only to his waist." The Dutch discoverers of Cape Horn a century later gave substance to the legend when they found the bones of a man they believed to have been over 3 m high. Jansson, however, is disappointingly discreet, filling out his chart with plausible-looking natives, rheas (the South American ostrich that they hunted with bows and spears), and penguins.

The checkerboard in the lower left corner is not evidence of local sophistication but rather represents a variable scale. This enabled sailors to counteract the increasingly exaggerated distances caused by high latitudes using Mercator's projection. (Campbell)

The Janssonius Family

Joannes Janssonius (Arnhem, 1588-1664), son of the Arnhem publisher Jan Janssen, married Elisabeth Hondius, daughter of Jodocus Hondius, in Amsterdam in 1612. After his marriage, he settled down in this town as a bookseller and publisher of cartographic material. In 1618, he established himself in Amsterdam next door to Blaeu’s bookshop. He entered into serious competition with Willem Jansz. Blaeu when copying Blaeu’s Licht der Zeevaert after the expiration of the privilege in 1620. His activities concerned the publication of atlases, books, single maps, and an extensive book trade with branches in Frankfurt, Danzig, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Berlin, Koningsbergen, Geneva, and Lyon. In 1631, he began publishing atlases together with Henricus Hondius.

In the early 1640s, Henricus Hondius left the atlas publishing business to Janssonius. Competition with Joan Blaeu, Willem’s son and successor, in atlas production, prompted Janssonius to enlarge his Atlas Novus finally into a work of six volumes, into which a sea atlas and an atlas of the Old World were inserted. Other atlases published by Janssonius are Mercator’s Atlas Minor, Hornius’s historical atlas (1652), the townbooks in eight volumes (1657), Cellarius’s Atlas Coelestis and several sea atlases and pilot guides.

After the death of Joannes Janssonius, the shop and publishing firm were continued by the heirs under the direction of Johannes van Waesbergen (c. 1616-1681), son-in-law of Joannes Janssonius. Van Waesbergen added Janssonius's name to his own.

In 1676, Joannes Janssonius’s heirs sold by auction “all the remaining Atlases in Latin, French, High and Low German, as well as the Stedeboecken in Latin, in 8 volumes, bound and unbound, maps, plates belonging to the Atlas and Stedeboecken.” The copperplates from Janssonius’s atlases were afterwards sold to Schenk and Valck.