Old antique map of Southeast Asia by Jan Huygen van Linschoten. oriented to the East 1596

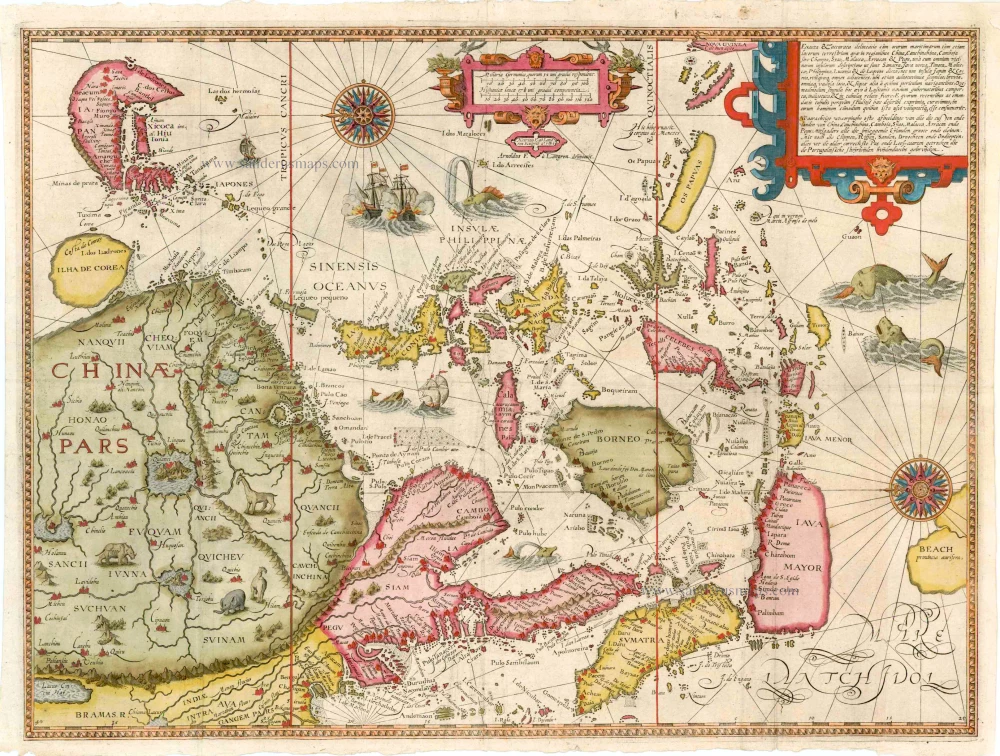

This map of the Indonesian archipelago and the Far East was designed by Arnold Floris van Langren, and engraved by his brother Hendrik in 1595.

"This map covers the entire Far East, from Java to Japan. A scale of degrees is provided along the upper and lower edge, indicating latitude at intervals of 5°. A cartouche in the upper right corner contains a bilingual title summarizing the territories depicted here (in translation): 'The true depiction or illustration of all the coasts and lands of China, Cochin China, Cambodia, Siam, Malacca, Arracan and Pegu, likewise of all the adjacent islands, large and small, together with the cliffs, riffs, sands, dry parts and shallows; all taken from the most accurate sea charts and rutters in use by the Portugese pilots today'. A cartouche in the middle along the upper edge contains scale bars in Dutch and Spanish miles and below these the name of the engraver with the year and the date of the design. The seas contain drawings of ships and sea monsters as well as two fully drawn compass roses.

This map of 1595 is one of the earliest engraved maps presenting the Portuguese knowledge of this area with such accuracy. The left half of Petrus Plancius's 1592 map of the Moluccas served as the model for the depiction of the Philippines, a large part of the presentday Indonesian archipelago, and the islands lying in between up to the Tropic of Cancer. When composing his map, Plancius made use of manuscript maps by the Portuguese cosmographer and mapmaker Bartolomeu Lasso. Just like the map in the Itinerario, Lasso also shows the entire island of Sumatra and a larger section of the continent from the Bay of Bengal to the coast of China at a latitude of 27°N.

Thus, the map in the Itinerario runs further to the west, but it reaches much less far to the east than Plancius's map. It does not show the numerous island groups in the Pacific Ocean. The hatching on the south coast of Java (JAVA MAYOR) and the east coasts of Borneo and Celebes indicates that these are unknown territories. Bali bears the name Galle, and Sumbawa is called by its old name IAVA MENOR. Halmahera (GILOLO) is shown correctly, though it is too big in relation to the whole. To the southeast of this point, hatching is used to draw an island called OS PAPUAS, which should actually be the beginning of New Guinea. A notable improvement over the older maps is the completion of the mapping of the Philippines. When the Spanish administration was moved from Goa to Manila, the gaps in knowledge about this island archipelago were considerably reduced, and existing information was improved. These advances in knowledge reached Europe through Portuguese maps and found their way into the printed maps, among other sources. Plancius's map and the map in the Itinerario must be counted among the earliest ones to reflect the up-dated information on the Philippines into account.

The map in the Itinerario also includes Korea and Japan in the north. Korea is drawn as a large circular island. The coasts are hatched, indicating that knowledge about this region was still unreliable. Even the correct shape of the northern regions of Japan was still a mystery to people. A very characteristic element shown here is the ebi-shape [= Japanes for shrimp] of Honshu, a drawing that was based on the representations in the cartographic work of the Portuguese mapmaker Fernão Vaz Dourado. Here, Hendrik Floris van Langren engraved a representation of Japan, which had become out of date in the meantime because a new map of Japan was published in the same year, 1595, in the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Luis Teixera made the original drawing available to Abraham Ortelius in 1591 or early in 1592. The map in the Itenerario also shows a larger part of the Chinese interior than shown on Plancius's printed map of the Moluccas. We may assume here that this extension was based on the example of Ortelius's map of China from 1584. That map had been composed with the aid of information from Jorge de Barbuda, a Portuguese in the service of Philip II of Spain." (Schilder)

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1562-c.1611)

Jan Huygen van Linschoten was one of the pathfinders for the first Dutch voyages to the East. Born in Haarlem, his parents moved to Enkhuizen in or after 1572 for political and religious reasons. In 1579 he left for Spain, where his older brothers had already been living for several years. In 1583, Jan Huygen set sail with a fleet heading for Goa in India. There he entered the service of the new archbishop.

The years that Jan Huygen spent in Goa, the administrative centre of Portugal’s widespread colonial territory in the East, provided an excellent opportunity to collect a wealth of information. Ships from all directions came into port here, and he could inform himself on the patterns of trade and the economic opportunities to China and Japan. In the foreword to his Itinerario (1596), Jan Huygen refers to the fact that he could not help but take note of everything. For instance, during his six-year sojourn in Goa, he also drew a bird’s eye view of this city, which he included in the Itinerario. He also gave ample attention to the Portuguese sailing routes to, from, and within Asian waters.

In November 1588 he came back home with the pepper ship Santa Cruz. He interrupted this voyage after an eventful journey and spent two years on the island of Terceira. In 1592 he arrived back in Enkhuizen. With his writings, drawings, and tales, he captured the attention of the town, and people encouraged him to publish the report of his journey.

While preparations for the publication of the Itinerario were in full swing, Jan Huygen took part in the first two polar expeditions as a chief commercial officer on the ships fitted out by Enkhuizen.

After these voyages, Jan Huygen stayed on land. He married with Reynu Meinertsdr Semeyns, daughter of one of Enkhuizen’s regent families. Thanks to his in-laws, he subsequently occupied various positions in the city’s civil administration until he died in 1611.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten and his Itinerario (1595-96).

By the time Jan Huygen returned from India, commercial and scientific circles in the Northern Netherlands were strongly motivated to learn more about overseas territories. He came in contact with the Amsterdam publisher Cornelis Claesz, who had been the publisher of Waghenaer’s cartographic work since 1589. Claesz showed great interest in Van Linschoten’s plans. He realized that on the threshold of a new era, cartographic and maritime works would be in high demand in circles of navigators, merchants, and other interested parties. Van Linschoten’s work could also serve as a guide to unknown territories.

On 14 March 1594, shortly before leaving northbound, Van Linschoten and Claesz signed a contract to print a book on navigation to the East Indies. By the end of this year, the States General granted Jan Huygen a ten-year privilege on the publication of his Itinerario and Reysgeschrift.

The volume published under the title Itinerario would include Van Linschoten’s travel account, supplemented by further information on the peoples, flora, and fauna of the Asian territories. Cornelis Claesz expanded the work and gave some attention to the west coast of Africa and also to America, a territory completely unknown to Van Linschoten. Because Jan Huygen had never been in these areas himself, Bernardus Paludanus was called in to help out. With the aid of Portuguese and Spanish sources, Paludanus and Van Linschoten made a compendium entitled Beschryvinghe van de gantsche Custe van Guinea.

The result of all this was a set of four different and distinctly separate individuals works. Each work has its own title page, its own date of publication, and a dedication. These four parts are usually bound in a single volume, with the Itinerario coming first. Therefore, the contents of the whole work are generally referred to by that name.

The Van Doetecum brothers engraved Jan Huygens drawings. Joannes van Doetecum had already engraved the world map of Petrus Plancius in 1594. Cornelis Claesz included this map in some copies of the 1596-99 editions. Still, in some copies, it was replaced by a map by Joan Baptista Vrients, engraved by the Van Langren brothers. The five detail maps, all of which were engraved by Arnold Floris and Hendrik Floris van Langren, cover a large proportion of the non-European world known at the time.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerarium was one of the most impressive works to be published at the end of the sixteenth century. The report of his northern travels appeared a couple of years later.

Exacta & accurata delineatio cum orarum maritimarum ... China, Cauchinchina ... nec non insulae Japan & Corea..

Item Number: 7026 Authenticity Guarantee

Category: Antique maps > Australia

Old, antique map of Southeast Asia by J.H. van Linschoten, oriented to the East

Date of the first edition: 1596

Date of this map: 1596

Copper engraving

Size: 39 x 52.5cm (15.2 x 20.5 inches)

Verso: Blank

Condition: Contemporary old coloured, tiny holes at fold junctions.

Condition Rating: A

References: Schilder 7, 10.3.6 - Afb. 10.40; Parry, p.87, Pl..4.2; Durant-Curtis, #15.

From: Jan Huygen van Linschoten, Itinerario, Voyage ofte Schipvaert naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien.... Amsterdam: C. Claesz, 1595-96.

This map of the Indonesian archipelago and the Far East was designed by Arnold Floris van Langren, and engraved by his brother Hendrik in 1595.

"This map covers the entire Far East, from Java to Japan. A scale of degrees is provided along the upper and lower edge, indicating latitude at intervals of 5°. A cartouche in the upper right corner contains a bilingual title summarizing the territories depicted here (in translation): 'The true depiction or illustration of all the coasts and lands of China, Cochin China, Cambodia, Siam, Malacca, Arracan and Pegu, likewise of all the adjacent islands, large and small, together with the cliffs, riffs, sands, dry parts and shallows; all taken from the most accurate sea charts and rutters in use by the Portugese pilots today'. A cartouche in the middle along the upper edge contains scale bars in Dutch and Spanish miles and below these the name of the engraver with the year and the date of the design. The seas contain drawings of ships and sea monsters as well as two fully drawn compass roses.

This map of 1595 is one of the earliest engraved maps presenting the Portuguese knowledge of this area with such accuracy. The left half of Petrus Plancius's 1592 map of the Moluccas served as the model for the depiction of the Philippines, a large part of the present-day Indonesian archipelago, and the islands lying in between up to the Tropic of Cancer. When composing his map, Plancius made use of manuscript maps by the Portuguese cosmographer and mapmaker Bartolomeu Lasso. Just like the map in the Itinerario, Lasso also shows the entire island of Sumatra and a larger section of the continent from the Bay of Bengal to the coast of China at a latitude of 27°N.

Thus, the map in the Itinerario runs further to the west, but it reaches much less far to the east than Plancius's map. It does not show the numerous island groups in the Pacific Ocean. The hatching on the south coast of Java (JAVA MAYOR) and the east coasts of Borneo and Celebes indicates that these are unknown territories. Bali bears the name Galle, and Sumbawa is called by its old name IAVA MENOR. Halmahera (GILOLO) is shown correctly, though it is too big in relation to the whole. To the southeast of this point, hatching is used to draw an island called OS PAPUAS, which should actually be the beginning of New Guinea. A notable improvement over the older maps is the completion of the mapping of the Philippines. When the Spanish administration was moved from Goa to Manila, the gaps in knowledge about this island archipelago were considerably reduced, and existing information was improved. These advances in knowledge reached Europe through Portuguese maps and found their way into the printed maps, among other sources. Plancius's map and the map in the Itinerario must be counted among the earliest ones to reflect the up-dated information on the Philippines into account.

The map in the Itinerario also includes Korea and Japan in the north. Korea is drawn as a large circular island. The coasts are hatched, indicating that knowledge about this region was still unreliable. Even the correct shape of the northern regions of Japan was still a mystery to people. A very characteristic element shown here is the ebi-shape [= Japanes for shrimp] of Honshu, a drawing that was based on the representations in the cartographic work of the Portuguese mapmaker Fernão Vaz Dourado. Here, Hendrik Floris van Langren engraved a representation of Japan, which had become out of date in the meantime because a new map of Japan was published in the same year, 1595, in the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Luis Teixera made the original drawing available to Abraham Ortelius in 1591 or early in 1592. The map in the Itenerario also shows a larger part of the Chinese interior than shown on Plancius's printed map of the Moluccas. We may assume here that this extension was based on the example of Ortelius's map of China from 1584. That map had been composed with the aid of information from Jorge de Barbuda, a Portuguese in the service of Philip II of Spain." (Schilder)

This map of the Indonesian archipelago and the Far East was designed by Arnold Floris van Langren, and engraved by his brother Hendrik in 1595.

"This map covers the entire Far East, from Java to Japan. A scale of degrees is provided along the upper and lower edge, indicating latitude at intervals of 5°. A cartouche in the upper right corner contains a bilingual title summarizing the territories depicted here (in translation): 'The true depiction or illustration of all the coasts and lands of China, Cochin China, Cambodia, Siam, Malacca, Arracan and Pegu, likewise of all the adjacent islands, large and small, together with the cliffs, riffs, sands, dry parts and shallows; all taken from the most accurate sea charts and rutters in use by the Portugese pilots today'. A cartouche in the middle along the upper edge contains scale bars in Dutch and Spanish miles and below these the name of the engraver with the year and the date of the design. The seas contain drawings of ships and sea monsters as well as two fully drawn compass roses.

This map of 1595 is one of the earliest engraved maps presenting the Portuguese knowledge of this area with such accuracy. The left half of Petrus Plancius's 1592 map of the Moluccas served as the model for the depiction of the Philippines, a large part of the presentday Indonesian archipelago, and the islands lying in between up to the Tropic of Cancer. When composing his map, Plancius made use of manuscript maps by the Portuguese cosmographer and mapmaker Bartolomeu Lasso. Just like the map in the Itinerario, Lasso also shows the entire island of Sumatra and a larger section of the continent from the Bay of Bengal to the coast of China at a latitude of 27°N.

Thus, the map in the Itinerario runs further to the west, but it reaches much less far to the east than Plancius's map. It does not show the numerous island groups in the Pacific Ocean. The hatching on the south coast of Java (JAVA MAYOR) and the east coasts of Borneo and Celebes indicates that these are unknown territories. Bali bears the name Galle, and Sumbawa is called by its old name IAVA MENOR. Halmahera (GILOLO) is shown correctly, though it is too big in relation to the whole. To the southeast of this point, hatching is used to draw an island called OS PAPUAS, which should actually be the beginning of New Guinea. A notable improvement over the older maps is the completion of the mapping of the Philippines. When the Spanish administration was moved from Goa to Manila, the gaps in knowledge about this island archipelago were considerably reduced, and existing information was improved. These advances in knowledge reached Europe through Portuguese maps and found their way into the printed maps, among other sources. Plancius's map and the map in the Itinerario must be counted among the earliest ones to reflect the up-dated information on the Philippines into account.

The map in the Itinerario also includes Korea and Japan in the north. Korea is drawn as a large circular island. The coasts are hatched, indicating that knowledge about this region was still unreliable. Even the correct shape of the northern regions of Japan was still a mystery to people. A very characteristic element shown here is the ebi-shape [= Japanes for shrimp] of Honshu, a drawing that was based on the representations in the cartographic work of the Portuguese mapmaker Fernão Vaz Dourado. Here, Hendrik Floris van Langren engraved a representation of Japan, which had become out of date in the meantime because a new map of Japan was published in the same year, 1595, in the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Luis Teixera made the original drawing available to Abraham Ortelius in 1591 or early in 1592. The map in the Itenerario also shows a larger part of the Chinese interior than shown on Plancius's printed map of the Moluccas. We may assume here that this extension was based on the example of Ortelius's map of China from 1584. That map had been composed with the aid of information from Jorge de Barbuda, a Portuguese in the service of Philip II of Spain." (Schilder)

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1562-c.1611)

Jan Huygen van Linschoten was one of the pathfinders for the first Dutch voyages to the East. Born in Haarlem, his parents moved to Enkhuizen in or after 1572 for political and religious reasons. In 1579 he left for Spain, where his older brothers had already been living for several years. In 1583, Jan Huygen set sail with a fleet heading for Goa in India. There he entered the service of the new archbishop.

The years that Jan Huygen spent in Goa, the administrative centre of Portugal’s widespread colonial territory in the East, provided an excellent opportunity to collect a wealth of information. Ships from all directions came into port here, and he could inform himself on the patterns of trade and the economic opportunities to China and Japan. In the foreword to his Itinerario (1596), Jan Huygen refers to the fact that he could not help but take note of everything. For instance, during his six-year sojourn in Goa, he also drew a bird’s eye view of this city, which he included in the Itinerario. He also gave ample attention to the Portuguese sailing routes to, from, and within Asian waters.

In November 1588 he came back home with the pepper ship Santa Cruz. He interrupted this voyage after an eventful journey and spent two years on the island of Terceira. In 1592 he arrived back in Enkhuizen. With his writings, drawings, and tales, he captured the attention of the town, and people encouraged him to publish the report of his journey.

While preparations for the publication of the Itinerario were in full swing, Jan Huygen took part in the first two polar expeditions as a chief commercial officer on the ships fitted out by Enkhuizen.

After these voyages, Jan Huygen stayed on land. He married with Reynu Meinertsdr Semeyns, daughter of one of Enkhuizen’s regent families. Thanks to his in-laws, he subsequently occupied various positions in the city’s civil administration until he died in 1611.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten and his Itinerario (1595-96).

By the time Jan Huygen returned from India, commercial and scientific circles in the Northern Netherlands were strongly motivated to learn more about overseas territories. He came in contact with the Amsterdam publisher Cornelis Claesz, who had been the publisher of Waghenaer’s cartographic work since 1589. Claesz showed great interest in Van Linschoten’s plans. He realized that on the threshold of a new era, cartographic and maritime works would be in high demand in circles of navigators, merchants, and other interested parties. Van Linschoten’s work could also serve as a guide to unknown territories.

On 14 March 1594, shortly before leaving northbound, Van Linschoten and Claesz signed a contract to print a book on navigation to the East Indies. By the end of this year, the States General granted Jan Huygen a ten-year privilege on the publication of his Itinerario and Reysgeschrift.

The volume published under the title Itinerario would include Van Linschoten’s travel account, supplemented by further information on the peoples, flora, and fauna of the Asian territories. Cornelis Claesz expanded the work and gave some attention to the west coast of Africa and also to America, a territory completely unknown to Van Linschoten. Because Jan Huygen had never been in these areas himself, Bernardus Paludanus was called in to help out. With the aid of Portuguese and Spanish sources, Paludanus and Van Linschoten made a compendium entitled Beschryvinghe van de gantsche Custe van Guinea.

The result of all this was a set of four different and distinctly separate individuals works. Each work has its own title page, its own date of publication, and a dedication. These four parts are usually bound in a single volume, with the Itinerario coming first. Therefore, the contents of the whole work are generally referred to by that name.

The Van Doetecum brothers engraved Jan Huygens drawings. Joannes van Doetecum had already engraved the world map of Petrus Plancius in 1594. Cornelis Claesz included this map in some copies of the 1596-99 editions. Still, in some copies, it was replaced by a map by Joan Baptista Vrients, engraved by the Van Langren brothers. The five detail maps, all of which were engraved by Arnold Floris and Hendrik Floris van Langren, cover a large proportion of the non-European world known at the time.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerarium was one of the most impressive works to be published at the end of the sixteenth century. The report of his northern travels appeared a couple of years later.