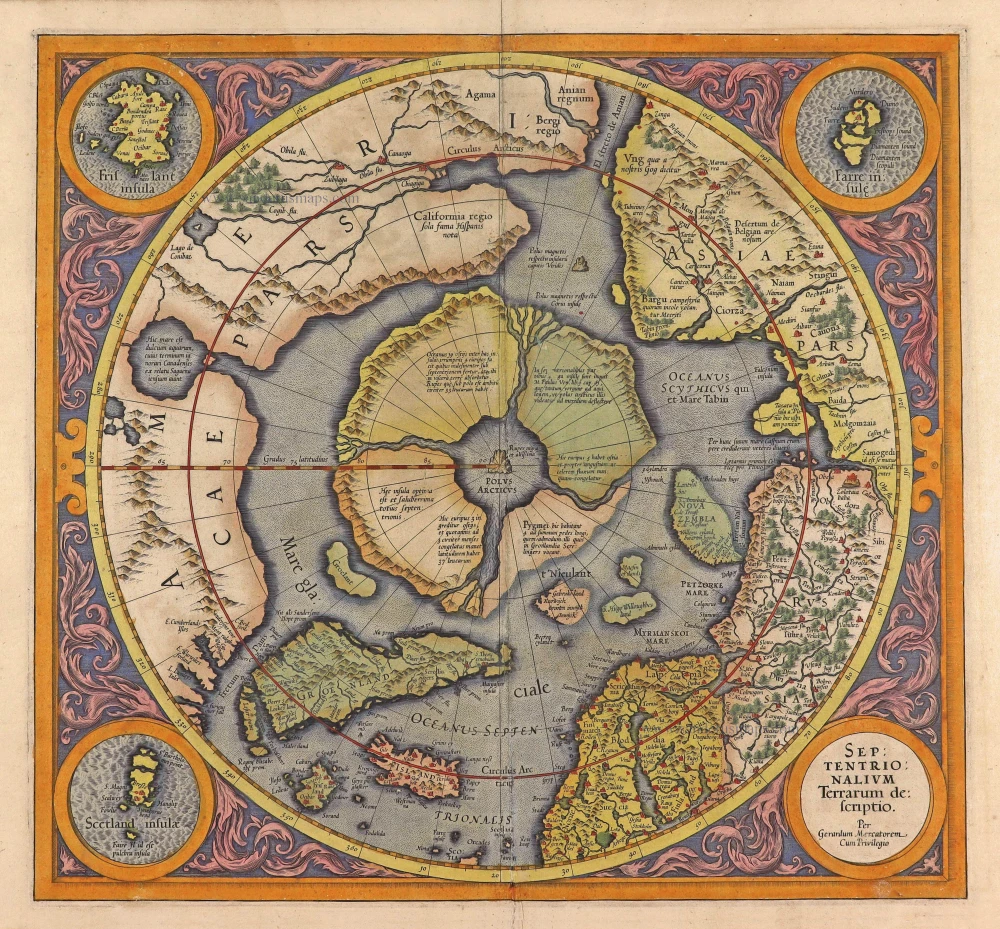

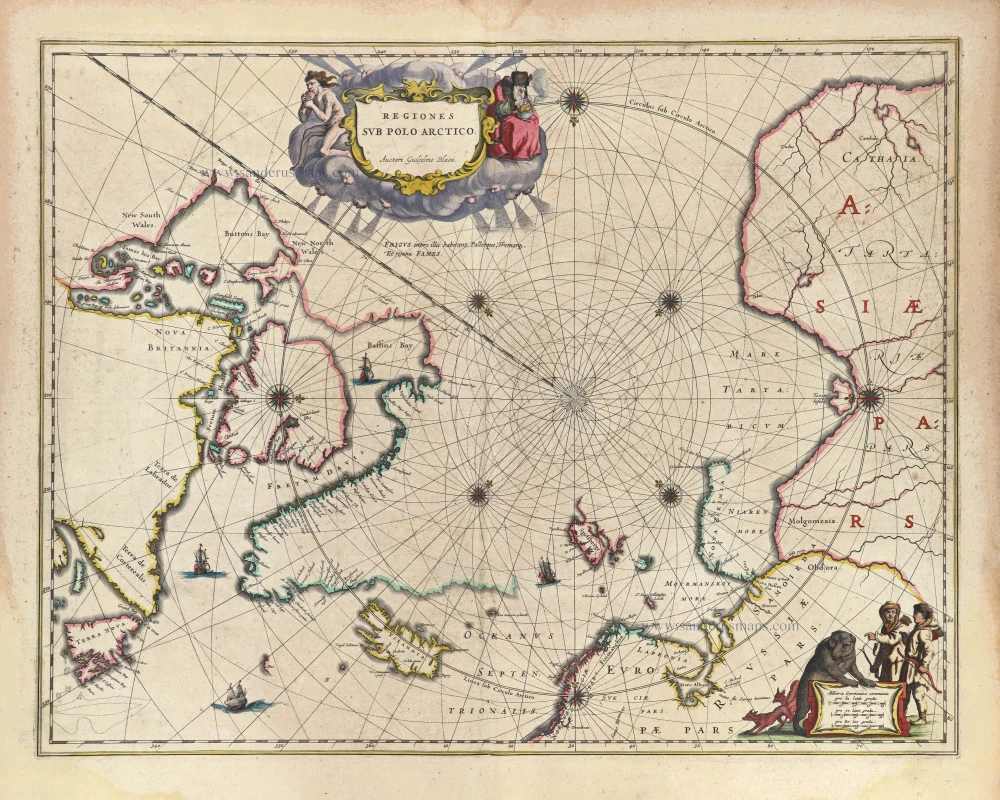

North Pole, by Gerard Mercator. 1623

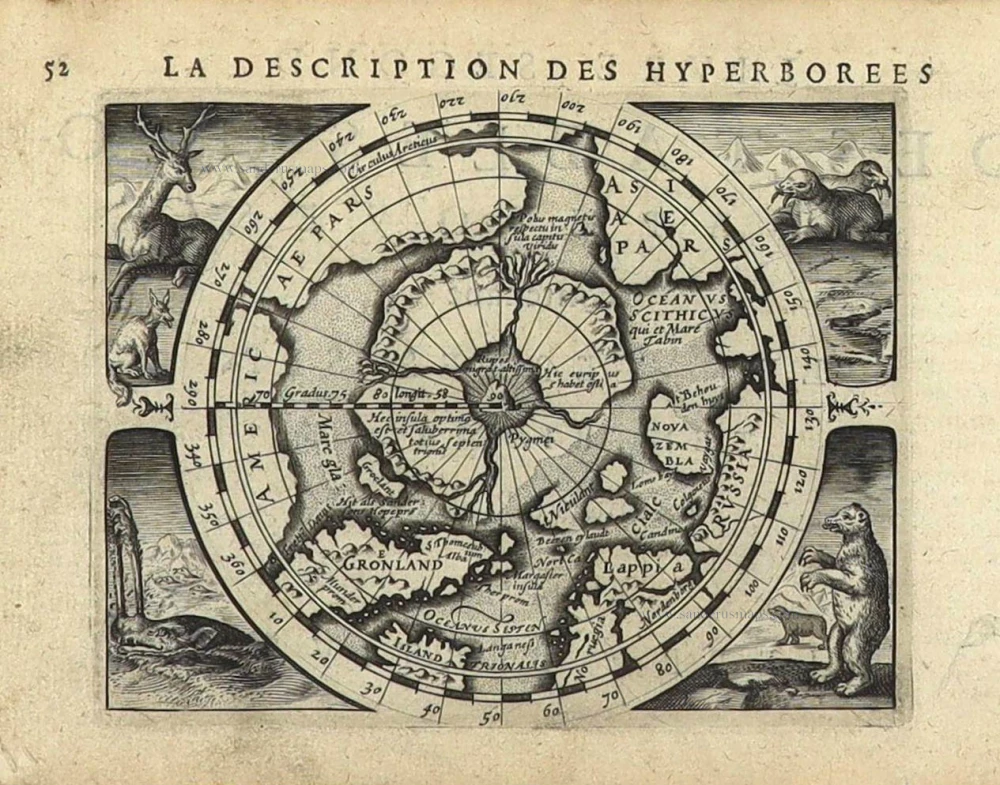

In the second half of the sixteenth-century polar geography became the subject of intense speculation. It was widely assumed that there was no land bridge between northeast Asia and northwest America and that the polar regions were separated from both continents by the sea. This was also the view taken by the foremost contemporary geographers, including Gerard Mercator, Abraham Ortelius and John Dee. The polar rock with its four surrounding islands separated by swirling torrents was universally accepted as real and can be seen, e.g. in the small map inset into Mercator's wall map of the world (1569) and Dee's polar map (c.1582).

This is the first map devoted to the Arctic. In the corners are four roundels; one of these contains the title, the other three have maps of the Faeroe Isles, the Shetland Isles and the mythical island of Frisland.

Second state with one island (lower right) with an incomplete coast.

Gerard Mercator (1512 – 1594)

Gerard Mercator was born Gerard de Cremere in Rupelmonde (near Antwerp) on 5 March 1512.

Young Gerard learned what Latin he could in Rupelmonde, and when he was about fifteen, his uncle sent him to s'Hertogenbosch to study at a school run by the Brothers of the Common Life. One of Mercator’s teachers was the celebrated humanist Macropedius. After three and a half years with the brothers, Gerard went to Louvain, where he enrolled in the university in 1530 as one of the poor students at Castle College.

By this time, he had Latinized his name to Mercator. He studied philosophy and took his master’s degree in 1532. The problems of the creation of the Universe and the Earth interested him in particular, and this is reflected in his works written in later years.

After spending a few years in Antwerp, he returned to Louvain in c. 1535, where he took courses in mathematics under Gemma Frisius. Soon, he was recognised as an expert on the construction of mathematical instruments, as a land surveyor and, after 1537, as a cartographer. He drew his income from these activities after his marriage on August 3, 1536. He also qualified himself as a copper engraver, the first to introduce italic handwriting to this trade. The first maps, drawn and engraved by Gerard Mercator, are Palestine, 1537; the World in double heart-shaped projection, 1538; and Flanders, 1540.

In 1544, Mercator came into great danger: he was arrested on the accusation of heresy and put into jail. Thanks to the intervention of the University of Louvain, he was released after four months. In 1552, he moved with his family to Duisburg (Germany). In 1560, Mercator became a cosmographer in service of the Duke of Jülich-Cleve-Berge, and in 1563, he became a lecturer at the Grammar School of the new University in Duisburg. During this period, he made wall maps of Europe, 1554; of Loraine, 1564; the British Isles, 1564; and the famous world map with increasing latitudes, 1569. About this time, Mercator was also working on the project for a complete description of the creation, the Heavens, Earth, Sea and world history. This resulted in his Atlas, sive cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura. He also worked on an edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia in 1578. The first part of his book, which contains modern maps (France, Germany, and the Netherlands), appeared in 1585.

Shortly after the publication of the second part of his map book (not yet called Atlas) with the maps of Italy (1589), he had a stroke that ended his highly significant productivity. The great man passed away on 2 December 1594, leaving the responsibility of finishing the map book to his son Rumold. The final part of it appeared in 1595. Its title is Pars Altera, and it constitutes an essential part of what was then called Mercator’s Atlas.

The map of Europe and the world map in the Atlas are by Rumold Mercator. After Rumold died in 1599, the Atlas was reissued in 1602.

The plates of the maps, both of the Ptolemy edition and the Atlas, were sold in 1604 to Jodocus Hondius of Amsterdam. The following year, Hondius managed to bring out Ptolemy’s Geographia. In 1606, the first Amsterdam edition of the Mercator Atlas appeared in the next year. From then to 1638, the Atlas saw many enlarged editions in various languages.

Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio.

Item Number: 28227 Authenticity Guarantee

Category: Antique maps > Europe > Northern Europe

Old, antique map of the North Pole, by Gerard Mercator.

Title: Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio.

Per Gerardum Mercatorem.

Cum Privilegio.

Cartographer: Gerard Mercator.

Date of the first edition: 1595.

Date of this map: 1613.

Copper engraving, printed on paper.

Size (not including margins): 370 x 400mm (14.57 x 15.75 inches)..

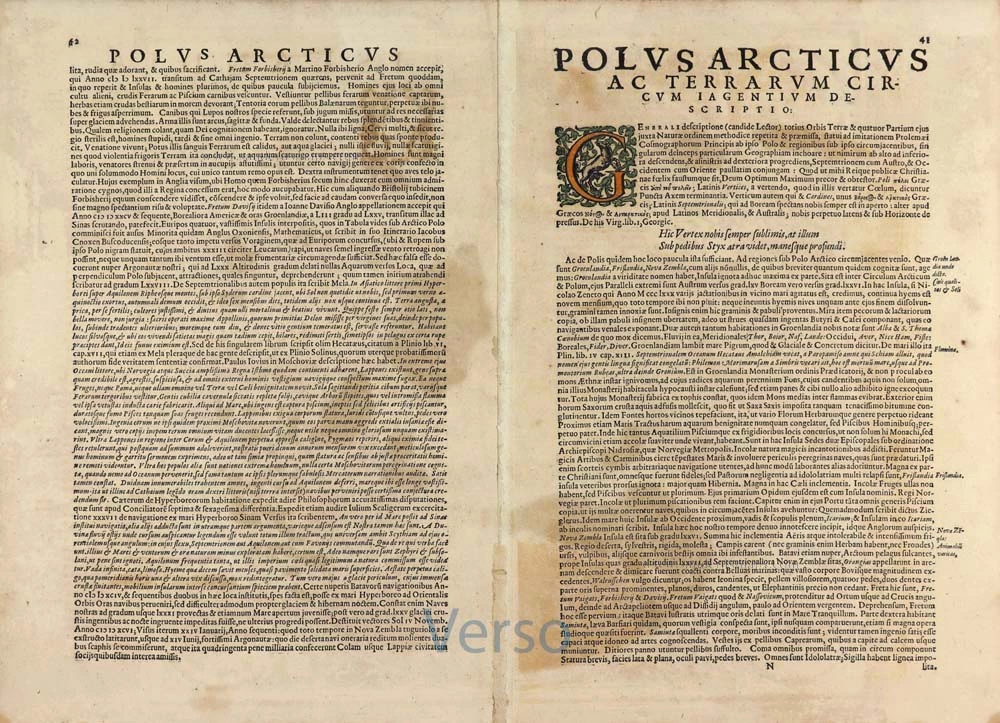

Verso: Latin text.

Condition: Original coloured, excellent.

Condition Rating: A+.

References: Van der Krogt 1, 0020:1A; Burden #88, State 2; Wagner, #177; Baynton-Williams New Worlds, p.53; Karrow, 56/142; Moreland-Bannister, p. 96

From: Gerardi Mercatoris - Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura. J. Hondius Jr. 1613. (Van der Krogt 1, 104)

In the second half of the sixteenth-century polar geography became the subject of intense speculation. It was widely assumed that there was no land bridge between northeast Asia and northwest America and that the polar regions were separated from both continents by the sea. This was also the view taken by the foremost contemporary geographers, including Gerard Mercator, Abraham Ortelius and John Dee. The polar rock with its four surrounding islands separated by swirling torrents was universally accepted as real and can be seen, e.g. in the small map inset into Mercator's wall map of the world (1569) and Dee's polar map (c.1582).

This is the first map devoted to the Arctic. In the corners are four roundels; one of these contains the title, the other three have maps of the Faeroe Isles, the Shetland Isles and the mythical island of Frisland.

Second state with one island (lower right) with an incomplete coast.

Gerard Mercator (1512 – 1594)

Gerard Mercator was born Gerard de Cremere in Rupelmonde (near Antwerp) on 5 March 1512.

Young Gerard learned what Latin he could in Rupelmonde, and when he was about fifteen, his uncle sent him to s'Hertogenbosch to study at a school run by the Brothers of the Common Life. One of Mercator’s teachers was the celebrated humanist Macropedius. After three and a half years with the brothers, Gerard went to Louvain, where he enrolled in the university in 1530 as one of the poor students at Castle College.

By this time, he had Latinized his name to Mercator. He studied philosophy and took his master’s degree in 1532. The problems of the creation of the Universe and the Earth interested him in particular, and this is reflected in his works written in later years.

After spending a few years in Antwerp, he returned to Louvain in c. 1535, where he took courses in mathematics under Gemma Frisius. Soon, he was recognised as an expert on the construction of mathematical instruments, as a land surveyor and, after 1537, as a cartographer. He drew his income from these activities after his marriage on August 3, 1536. He also qualified himself as a copper engraver, the first to introduce italic handwriting to this trade. The first maps, drawn and engraved by Gerard Mercator, are Palestine, 1537; the World in double heart-shaped projection, 1538; and Flanders, 1540.

In 1544, Mercator came into great danger: he was arrested on the accusation of heresy and put into jail. Thanks to the intervention of the University of Louvain, he was released after four months. In 1552, he moved with his family to Duisburg (Germany). In 1560, Mercator became a cosmographer in service of the Duke of Jülich-Cleve-Berge, and in 1563, he became a lecturer at the Grammar School of the new University in Duisburg. During this period, he made wall maps of Europe, 1554; of Loraine, 1564; the British Isles, 1564; and the famous world map with increasing latitudes, 1569. About this time, Mercator was also working on the project for a complete description of the creation, the Heavens, Earth, Sea and world history. This resulted in his Atlas, sive cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura. He also worked on an edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia in 1578. The first part of his book, which contains modern maps (France, Germany, and the Netherlands), appeared in 1585.

Shortly after the publication of the second part of his map book (not yet called Atlas) with the maps of Italy (1589), he had a stroke that ended his highly significant productivity. The great man passed away on 2 December 1594, leaving the responsibility of finishing the map book to his son Rumold. The final part of it appeared in 1595. Its title is Pars Altera, and it constitutes an essential part of what was then called Mercator’s Atlas.

The map of Europe and the world map in the Atlas are by Rumold Mercator. After Rumold died in 1599, the Atlas was reissued in 1602.

The plates of the maps, both of the Ptolemy edition and the Atlas, were sold in 1604 to Jodocus Hondius of Amsterdam. The following year, Hondius managed to bring out Ptolemy’s Geographia. In 1606, the first Amsterdam edition of the Mercator Atlas appeared in the next year. From then to 1638, the Atlas saw many enlarged editions in various languages.