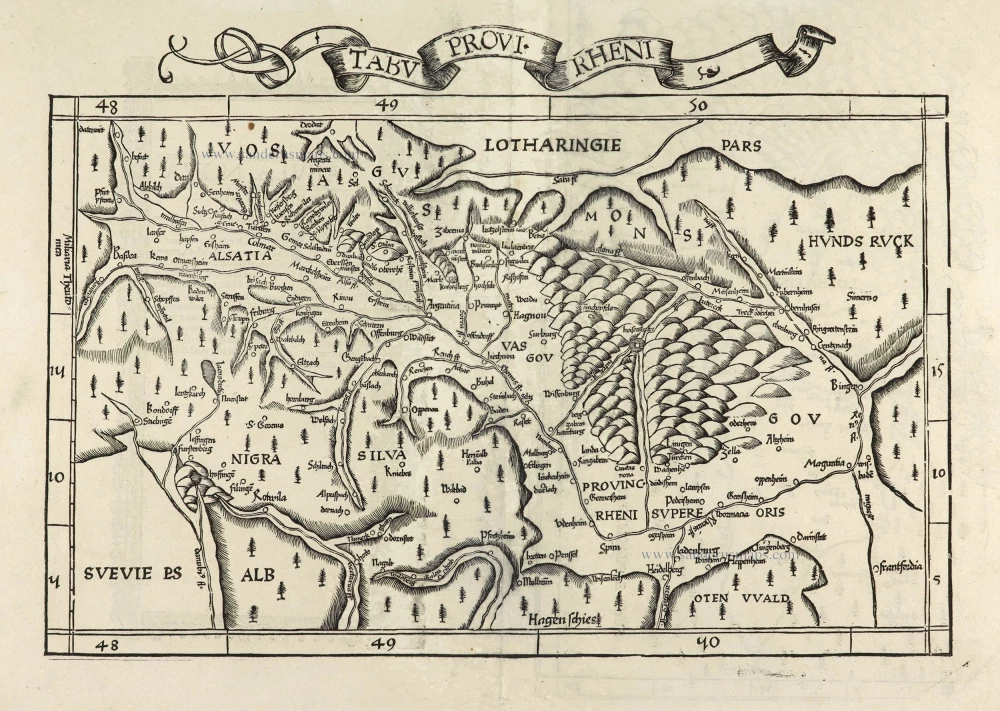

Rheinland-Pfalz (Lorraine on verso) by Lorenz Fries. 1525

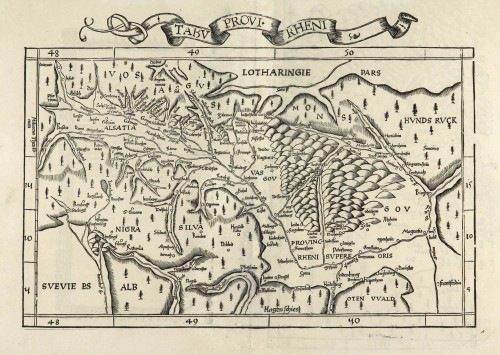

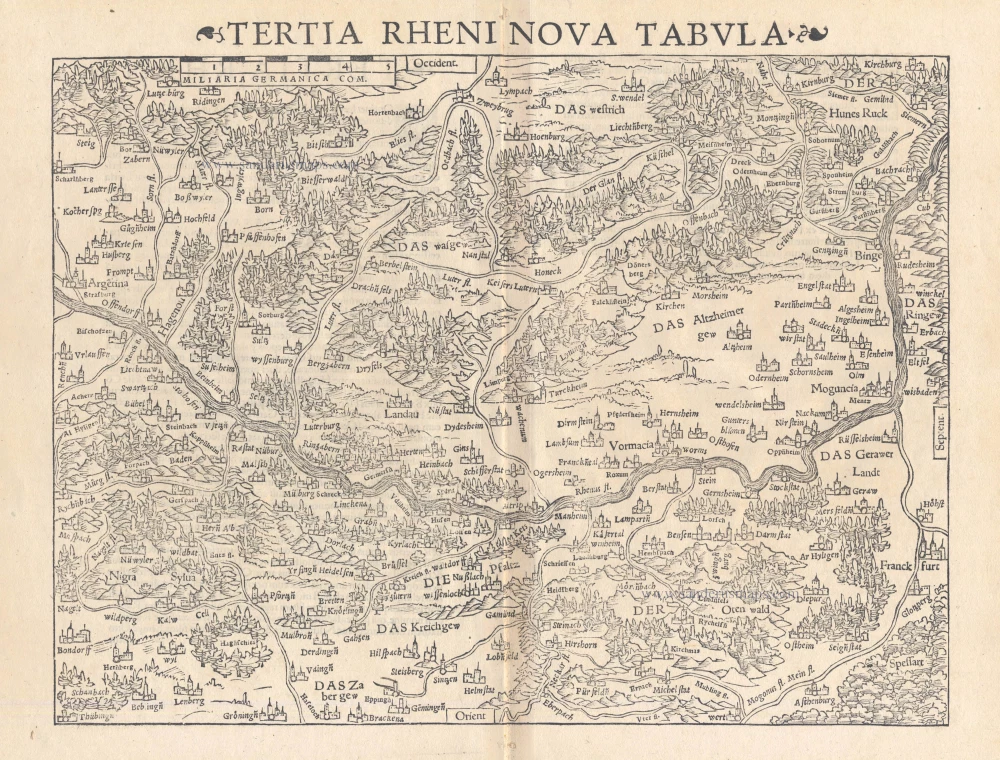

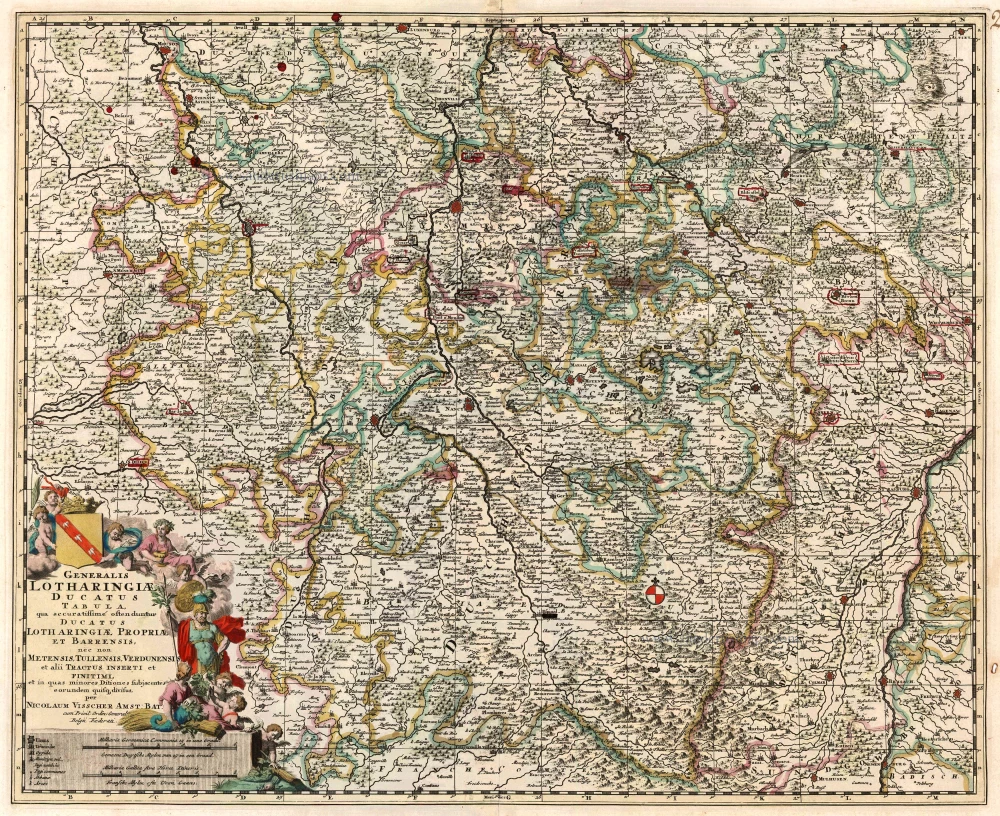

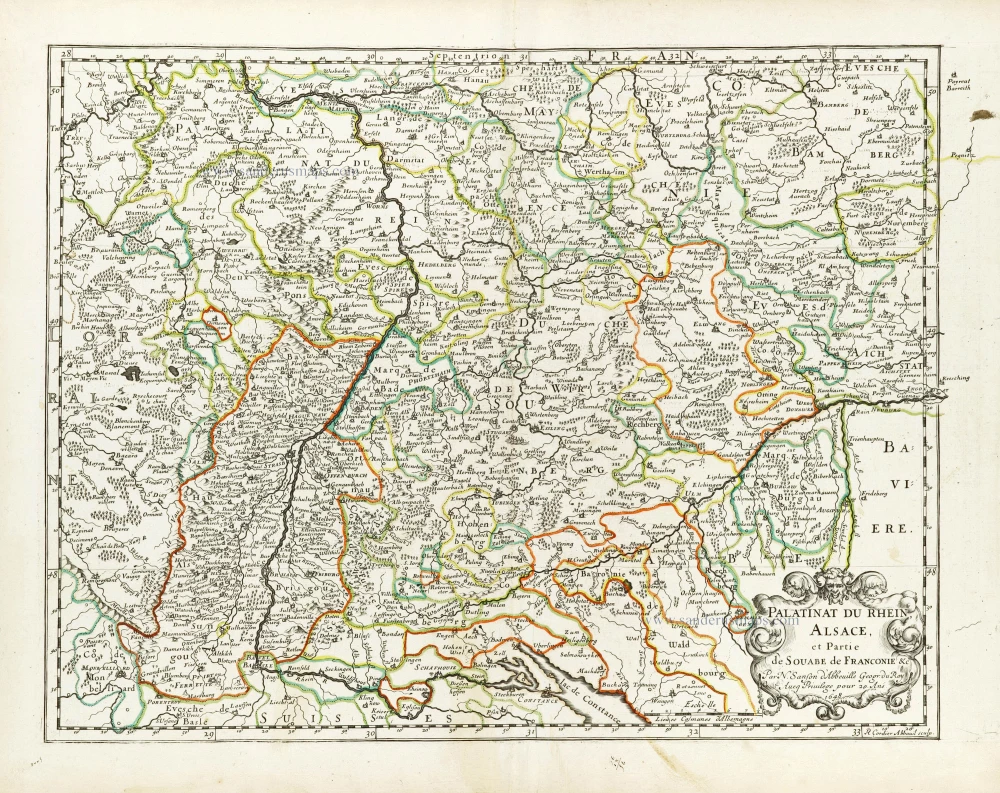

Second edition (of four) of this map, based on Waldseemüller's modern map of Rheinland-Pfalz.

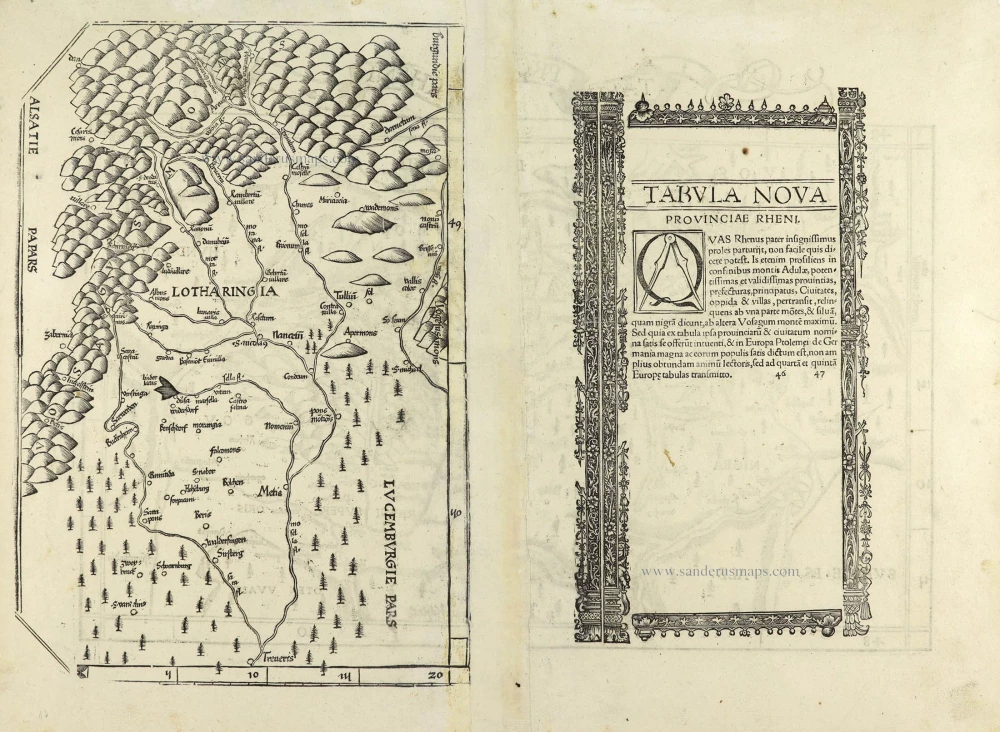

On the reverse, the text is contained within elaborate Renaissance woodcut panels, which may have been designed by Albrecht Dürer, the known contributor to diagrams elsewhere in the atlas.

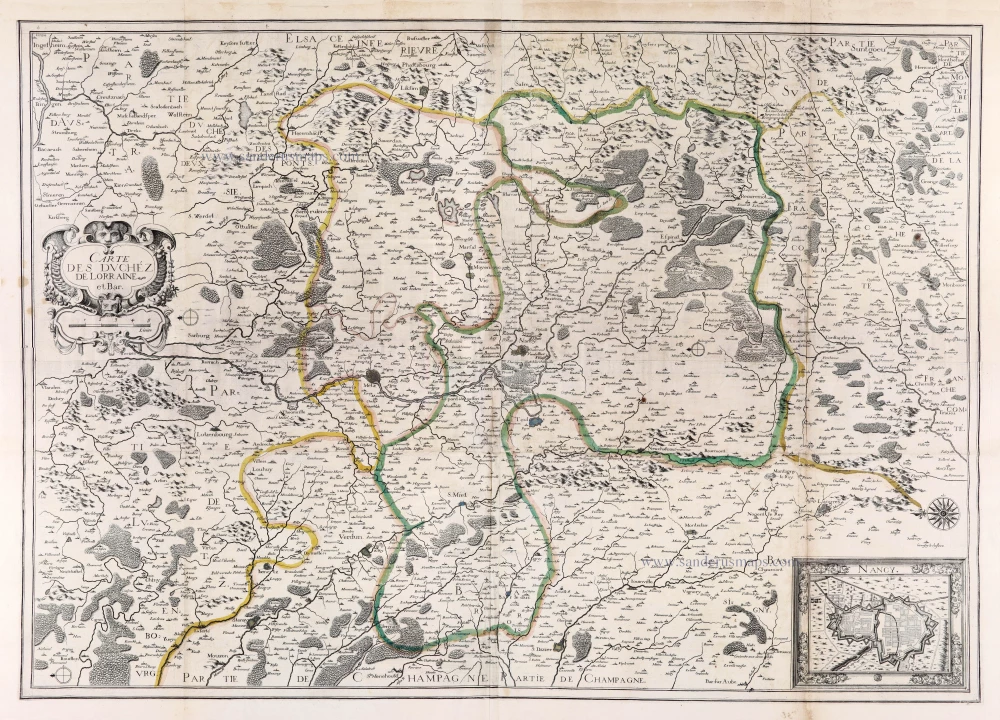

The verso's left side shows a Lorraine map, 33.5 x 23 cm.

Lorenz Fries* (c. 1485 – 1532)

Lorenz Fries, a physician, astrologer, and cartographic editor, was a native Alsatian. Nothing is known about his youth and early schooling. His university education in philosophy and medicine has been acquired at several schools. He probably attended Vienna, Montpellier, Piacenza, and Pavia. He obtained a Doctor of Arts degree at one of these institutions.

His first professional position was in Sélestat, near Strasbourg. He practised medicine in Colmar from 1514 to 1518. He wrote several medical works, including a practice entitled Spiegel der Artzny (Mirror of Medicine), a trendy book with seven editions up to 1546. After 1519, he moved to Strasbourg, where he stayed until about 1527.

In 1520, Fries became involved in publishing new editions of maps by Martin Waldseemüller. He collaborated with Peter Apian to publish a much-reduced version of Waldseemüller's map of 1507.

In the meantime, Fries was preparing a new edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. The book was printed in 1522 by Johannes Grüninger, an esteemed printer from Strasbourg who had previously published the Waldseemüller. It was based on Waldseemüller's editions of 1513 and 1520. Fries says in a note to the reader: "…, we declare that Martin Waldseemüller, piously deceased, originally constructed these maps and that they have been drawn in a format smaller than they ever had". The book sold well, and new editions would follow, printed with the same woodblocks.

In 1525, Willibald Pirkheimer, the Nuremberg humanist, published a new edition with Grüninger. The volume was published jointly with the Nuremberg printer Johannes Koberger. It included the same fifty Waldseemüller/Fries maps as the 1522 edition.

Michael Servetus (= Michael Villanovus) printed two more editions in Lyon in 1535 and 1541. Servetus was tried for heresy in 1553. One of the allegations was that he had written a statement on the verso of the map of the Holy Land describing it as primarily infertile. The idea originated in Fries's edition in 1522. Servetus was burned at the stake, and at Calvin's orders, many copies of Servetus's books followed him into the flames.

Fries also published other books on astrology and medicine. In addition, he undertook a reduction of Waldseemüller's large map of 1516, the Carta Marina Navigatoria, which he translated into German simultaneously. The map was published in 1525, but no copy of this edition survived. The earliest copy known is dated 1530.

In 1525, Strasbourg had become a thoroughly reformed city, and the Roman church's adherents found themselves increasingly unwelcome. For this reason, Fries probably renounced his citizenship and moved to Metz. During this period, he published his last two medical works.

*He should be distinct from the historian Lorenz Fries of Mergentheim (1491-1550).

Martin Waldseemüller (Ilacomilus) (c. 1473-1519)

Martin Walseemüller and his collaborator, Matthias Ringmann, are credited with the first recorded usage of the word America to name the New World in honour of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci.

He was born about 1475, most probably in the village of Wolfenweiler near Freiburg in Breisgau (southern Germany). He studied at the University of Freiburg, where he met Johann Scott, the future printer of Waldseemüller’s edition of Ptolemy and Matthias Ringman, a poet who wrote Waldseemüller’s texts. Gregor Reisch was their tutor. He was noted for his philosophical work, Margaretha Philosophica (1503), a widely read book that included a world map in Ptolemaic form. He undoubtedly aroused the students’ interest in cosmography.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Walseemüller moved to St.Dié in the Vosges. He Hellenized his name to Ilacomilus and worked on an edition of Ptolemy. He learned the printing trade in Basle and became a professor of cosmography under the patronage of René II, Duke of Lorraine.

Together with a group of scholars, among them were Nicholas Lud and Matthias Ringmann, they installed a printing press in St. Dié. The first book appeared in 1507: Cosmographiae Introductio… Few books have generated as much interest and speculation as this book because it suggested that the new continent is named America in honour of Amerigo Vespucci, whose letters about his American “discoveries” form a large part of the book. Great interest was also attached to the two maps on the title page constituting part of the Cosmographiae Introductio: a large 12-panel wall map of the world and a set of globe gores. The map and globe were notable for showing the New World as a continent separate from Asia and naming the southern landmass America.

Ringmann wrote the Cosmographiae Introductio's text, using the name ‘America’. He died in 1511, and by then, Waldseemüller was having doubts about the name they had coined.

In 1511, Walseemüller published the Carta Itineraria Europae, a road map of Europe that showed essential trade routes and pilgrim routes from central Europe to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It was the first printed wall map of Europe.

After Ringmann’s death, Waldseemüller concentrated on the new version of Ptolemy’s Geographia. Johannes Scott finally printed the new edition in 1513 in Strasbourg, and it is now regarded as the most important. Waldseemüller included twenty modern maps in the new Geographia as a separate appendix.

The 1507 wall map was lost for a long time, but Joseph Fischer found a copy in Schloss Wolfegg in southern Germany in 1901. It is the only known copy purchased by the United States Library of Congress in May 2003.

Tabu Provi. Rheni.

Item Number: 28200 Authenticity Guarantee

Category: Antique maps > Europe > Germany

Rheinland-Pfalz, by Lorenz Fries.

Lorraine on verso/

Title: Tabu Provi. Rheni.

Date of the first edition: 1522.

Date of this map: 1525.

Woodcut, printed on paper.

Size (not including margins and title): 265 x 430mm (10.43 x 16.93 inches).

Verso: Latin text.

Condition: Excellent.

Condition Rating: A.

References: Karrow, 28/48

From: L. Fries, Opus Geographiae. Strasbourg, J. Grüninger, 1525. (Karrow, 28/G.1; Shirley (Brit. Lib.), T.PTOL.7b))

Second edition (of four) of this map, based on Waldseemüller's modern map of Rheinland-Pfalz.

On the reverse, the text is contained within elaborate Renaissance woodcut panels, which may have been designed by Albrecht Dürer, the known contributor to diagrams elsewhere in the atlas.

The verso's left side shows a Lorraine map, 33.5 x 23 cm.

Lorenz Fries* (c. 1485 – 1532)

Lorenz Fries, a physician, astrologer, and cartographic editor, was a native Alsatian. Nothing is known about his youth and early schooling. His university education in philosophy and medicine has been acquired at several schools. He probably attended Vienna, Montpellier, Piacenza, and Pavia. He obtained a Doctor of Arts degree at one of these institutions.

His first professional position was in Sélestat, near Strasbourg. He practised medicine in Colmar from 1514 to 1518. He wrote several medical works, including a practice entitled Spiegel der Artzny (Mirror of Medicine), a trendy book with seven editions up to 1546. After 1519, he moved to Strasbourg, where he stayed until about 1527.

In 1520, Fries became involved in publishing new editions of maps by Martin Waldseemüller. He collaborated with Peter Apian to publish a much-reduced version of Waldseemüller's map of 1507.

In the meantime, Fries was preparing a new edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. The book was printed in 1522 by Johannes Grüninger, an esteemed printer from Strasbourg who had previously published the Waldseemüller. It was based on Waldseemüller's editions of 1513 and 1520. Fries says in a note to the reader: "…, we declare that Martin Waldseemüller, piously deceased, originally constructed these maps and that they have been drawn in a format smaller than they ever had". The book sold well, and new editions would follow, printed with the same woodblocks.

In 1525, Willibald Pirkheimer, the Nuremberg humanist, published a new edition with Grüninger. The volume was published jointly with the Nuremberg printer Johannes Koberger. It included the same fifty Waldseemüller/Fries maps as the 1522 edition.

Michael Servetus (= Michael Villanovus) printed two more editions in Lyon in 1535 and 1541. Servetus was tried for heresy in 1553. One of the allegations was that he had written a statement on the verso of the map of the Holy Land describing it as primarily infertile. The idea originated in Fries's edition in 1522. Servetus was burned at the stake, and at Calvin's orders, many copies of Servetus's books followed him into the flames.

Fries also published other books on astrology and medicine. In addition, he undertook a reduction of Waldseemüller's large map of 1516, the Carta Marina Navigatoria, which he translated into German simultaneously. The map was published in 1525, but no copy of this edition survived. The earliest copy known is dated 1530.

In 1525, Strasbourg had become a thoroughly reformed city, and the Roman church's adherents found themselves increasingly unwelcome. For this reason, Fries probably renounced his citizenship and moved to Metz. During this period, he published his last two medical works.

*He should be distinct from the historian Lorenz Fries of Mergentheim (1491-1550).

Martin Waldseemüller (Ilacomilus) (c. 1473-1519)

Martin Walseemüller and his collaborator, Matthias Ringmann, are credited with the first recorded usage of the word America to name the New World in honour of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci.

He was born about 1475, most probably in the village of Wolfenweiler near Freiburg in Breisgau (southern Germany). He studied at the University of Freiburg, where he met Johann Scott, the future printer of Waldseemüller’s edition of Ptolemy and Matthias Ringman, a poet who wrote Waldseemüller’s texts. Gregor Reisch was their tutor. He was noted for his philosophical work, Margaretha Philosophica (1503), a widely read book that included a world map in Ptolemaic form. He undoubtedly aroused the students’ interest in cosmography.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Walseemüller moved to St.Dié in the Vosges. He Hellenized his name to Ilacomilus and worked on an edition of Ptolemy. He learned the printing trade in Basle and became a professor of cosmography under the patronage of René II, Duke of Lorraine.

Together with a group of scholars, among them were Nicholas Lud and Matthias Ringmann, they installed a printing press in St. Dié. The first book appeared in 1507: Cosmographiae Introductio… Few books have generated as much interest and speculation as this book because it suggested that the new continent is named America in honour of Amerigo Vespucci, whose letters about his American “discoveries” form a large part of the book. Great interest was also attached to the two maps on the title page constituting part of the Cosmographiae Introductio: a large 12-panel wall map of the world and a set of globe gores. The map and globe were notable for showing the New World as a continent separate from Asia and naming the southern landmass America.

Ringmann wrote the Cosmographiae Introductio's text, using the name ‘America’. He died in 1511, and by then, Waldseemüller was having doubts about the name they had coined.

In 1511, Walseemüller published the Carta Itineraria Europae, a road map of Europe that showed essential trade routes and pilgrim routes from central Europe to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It was the first printed wall map of Europe.

After Ringmann’s death, Waldseemüller concentrated on the new version of Ptolemy’s Geographia. Johannes Scott finally printed the new edition in 1513 in Strasbourg, and it is now regarded as the most important. Waldseemüller included twenty modern maps in the new Geographia as a separate appendix.

The 1507 wall map was lost for a long time, but Joseph Fischer found a copy in Schloss Wolfegg in southern Germany in 1901. It is the only known copy purchased by the United States Library of Congress in May 2003.